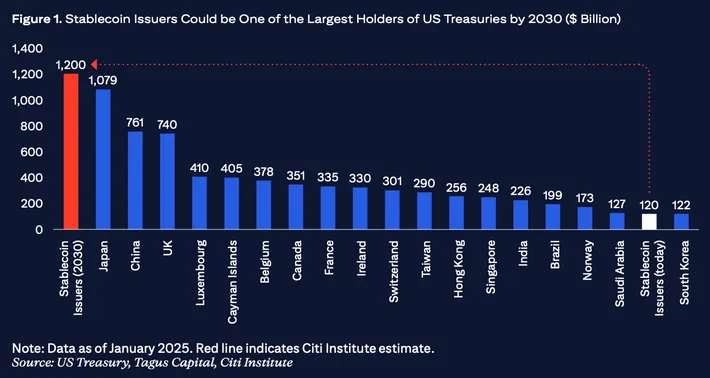

Stablecoin issuers have quietly become among the largest holders of short-term U.S. government debt, with Circle, Tether, and other major providers holding more than $120 billion in Treasury bills and related instruments as of mid-2025. This deep-dive investigation examines how the crypto industry's quest for stable digital dollars has created a direct financial pipeline between decentralized finance and the Federal Reserve's monetary operations.

When Circle published its July 2024 reserve attestation, crypto observers noticed something that would have seemed implausible just three years earlier. The company behind USD Coin (USDC), the second-largest stablecoin by market capitalization, reported holding $28.6 billion in its reserve fund. Of that total, $28.1 billion sat in short-dated U.S. Treasury securities and overnight reverse repurchase agreements with the Federal Reserve. The remaining $500 million existed as cash deposits at regulated financial institutions.

This composition represents more than prudent reserve management. It demonstrates how the stablecoin industry has fundamentally transformed into a specialized conduit for U.S. government debt, one that operates largely outside traditional banking supervision while generating billions in revenue from the spread between near-zero interest paid to stablecoin holders and the yields earned on Treasury instruments.

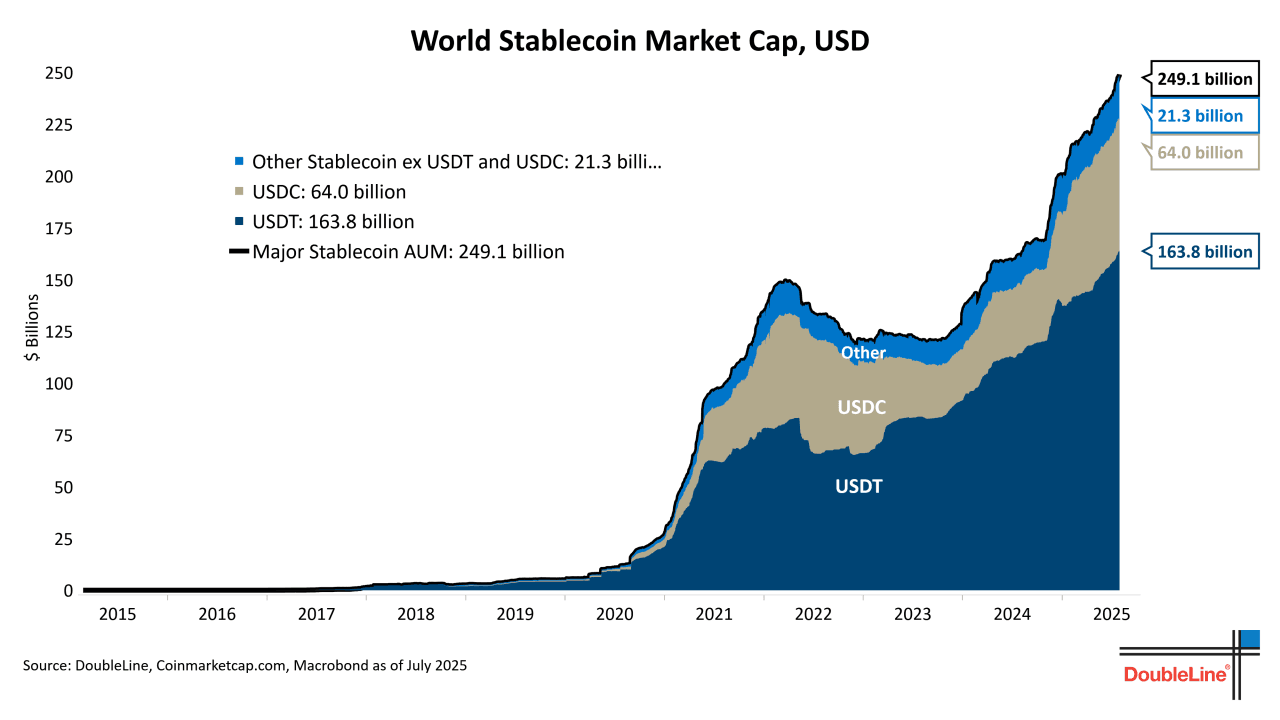

The numbers tell a striking story. Tether, the issuer of USDT and the world's largest stablecoin with roughly $120 billion in circulation as of October 2024, disclosed in its Q2 2024 transparency report that approximately 84.5% of its reserves consisted of cash, cash equivalents, and short-term Treasury bills. At that composition and scale, Tether alone would rank among the top 20 holders of U.S. government debt, exceeding the Treasury holdings of numerous sovereign nations.

Across the stablecoin ecosystem, this pattern repeats. Paxos, the regulated trust company issuing both USDP and managing reserves for Binance's BUSD before its wind-down, has maintained near-total Treasury exposure since 2021. Even newer entrants pursuing different stability mechanisms find themselves drawn to government debt. Ethena Labs, which launched its synthetic dollar USDe in late 2023, uses Delta-neutral derivatives positions but still maintains Treasury bill exposure as part of its backing strategy during periods of negative funding rates.

This convergence on Treasury instruments is not coincidental. It reflects a fundamental economic reality that has reshaped crypto's relationship with traditional finance: stablecoins have become, in practice, uninsured money market funds with instant redemption features, operating on blockchain rails and generating substantial profits from the delta between their cost of capital (functionally zero, since most stablecoins pay no interest) and the risk-free rate on short-term government securities.

The implications extend far beyond crypto. When stablecoin net new issuance surged by approximately $40 billion in the first half of 2024 (CoinGecko data), that capital flowed predominantly into Treasury markets, compressing yields on bills and influencing repo market dynamics. Conversely, during crypto market downturns when stablecoin redemptions accelerate, billions in Treasury positions must be liquidated, potentially amplifying volatility in money markets. The stablecoin sector has effectively inserted itself into the plumbing of U.S. monetary policy transmission, creating feedback loops that central bankers are only beginning to study.

Below we dive deep into how this quiet monetization occurred, who benefits from it, what risks it creates, and why the fusion of crypto rails and government debt markets represents one of the most consequential yet underexamined developments in digital finance. The story involves the mechanics of reserve management, the economics of yield capture, the emergence of tokenized Treasury products, and a regulatory apparatus struggling to keep pace with innovation that blurs the boundaries between securities, currencies, and payment systems.

Stablecoins and "Reserves"

To understand how stablecoins became vehicles for Treasury exposure, we must first establish what stablecoins are, how they maintain their pegs, and what "reserves" actually mean in this context.

At the most basic level, a stablecoin is a cryptocurrency designed to maintain a stable value relative to a reference asset, most commonly the U.S. dollar. Unlike Bitcoin or Ethereum, whose prices fluctuate based on market supply and demand, stablecoins aim to trade at or very near $1.00 per token at all times. This stability makes them useful for several purposes within crypto markets: as trading pairs on exchanges, as temporary stores of value during market volatility, as settlement mechanisms for decentralized finance protocols, and increasingly as payment instruments for cross-border transactions.

The stability mechanism, however, determines everything about a stablecoin's risk profile and reserve composition. The crypto industry has experimented with three broad categories of stablecoins, each with distinct approaches to maintaining the peg.

Fiat-Backed Stablecoins represent the dominant model and the focus of this analysis. These tokens promise 1:1 redeemability for U.S. dollars (or other fiat currencies) and claim to hold equivalent reserves in cash and highly liquid securities. USDC, USDT, USDP, and similar tokens fall into this category.

Users deposit dollars with the issuer (either directly or through authorized partners), and the issuer mints an equivalent number of tokens. When users want to redeem, they return tokens and receive dollars back. In theory, the reserves always equal or exceed the outstanding token supply, ensuring that every holder can redeem at par.

The critical question becomes: what assets constitute these reserves? Early stablecoins held primarily cash in bank accounts, but this approach proved economically inefficient for issuers. Cash deposits, particularly in a near-zero interest rate environment, generated minimal returns. Maintaining banking relationships required significant operational overhead. And most importantly, holding pure cash meant issuers earned nothing on billions in user deposits while bearing all operational costs and regulatory burdens.

This economic reality drove the migration toward short-duration securities. By the end of 2021, most major fiat-backed stablecoins had transitioned their reserve mix to prioritize overnight and short-term Treasury instruments, reverse repurchase agreements, and Treasury-only money market funds. These instruments offered key advantages: they generated meaningful yield in a rising interest rate environment (by 2023, 3-month Treasury bills yielded over 5%), they provided same-day or next-day liquidity for redemptions, they carried virtually zero credit risk due to government backing, and they faced lighter regulatory scrutiny than corporate bonds or commercial paper.

The attestation reports that stablecoin issuers publish monthly (or in some cases quarterly) provide windows into these reserve compositions, though the level of detail varies significantly. Circle's reports, prepared by accounting firm Deloitte, break down reserves into specific categories: Treasury securities by maturity, overnight reverse repo positions, and cash at specific banking institutions. Tether's assurance reports, prepared by BDO Italia, historically provided less granularity but have improved over time, now showing percentages allocated to Treasury bills versus money market funds versus other instruments.

Paxos, as a New York trust company, faces stricter disclosure requirements and publishes detailed monthly reports showing exact CUSIP identifiers for its Treasury holdings.

Algorithmic Stablecoins attempt to maintain pegs through market mechanisms and incentive systems rather than direct fiat backing. The catastrophic failure of TerraUSD (UST) in May 2022, which lost its peg and triggered a death spiral that destroyed roughly $40 billion in value, demonstrated the profound risks of this approach.

UST maintained its peg through an algorithmic relationship with its sister token LUNA; when confidence broke, both tokens collapsed in a cascading liquidation. This failure pushed the industry decisively toward over-collateralized or fiat-backed models and made regulators deeply skeptical of algorithmic approaches.

Synthetic or Crypto-Collateralized Stablecoins maintain their pegs using crypto assets as collateral, typically with over-collateralization requirements. DAI, created by MakerDAO, pioneered this model: users lock up cryptocurrency (like Ethereum) worth 150% or more of the DAI they wish to mint. If collateral values fall below required thresholds, the system liquidates positions to maintain backing. More recently, this model has evolved to include real-world assets. MakerDAO's transition toward integrating tokenized Treasury bills into DAI's backing demonstrates how even crypto-native models are gravitating toward government debt exposure.

For fiat-backed stablecoins that now dominate the market, the reserve composition directly determines both the safety of the peg and the economics of the business model. Issuers face a fundamental tension: they need sufficient liquidity to process redemptions quickly (which argues for overnight instruments and cash), but they also want to maximize yield on reserves (which argues for slightly longer-duration securities). This tension has largely been resolved in favor of short-dated Treasury exposure, typically overnight to 3-month maturities, which offers attractive yields while maintaining next-day liquidity.

The attestation process itself deserves scrutiny. These are not full audits in most cases. Attestations involve accountants examining whether the stated reserves exist at a specific point in time, but they typically do not verify the continuous adequacy of reserves, test internal controls, or assess the quality and liquidity of all assets.

Some critics argue this creates gaps in transparency. A company could theoretically optimize its balance sheet just before an attestation date, present favorable numbers, and then adjust positions afterward. However, the trend has been toward more frequent attestations and greater detail, particularly as regulatory pressure increases.

Understanding this foundation is essential because the shift from cash to Treasuries in stablecoin reserves represents more than a technical portfolio adjustment. It represents the crypto industry's integration into the apparatus of government debt monetization, with all the systemic implications that entails.

The Mechanics of Yield: How Treasury Exposure Generates Return

The transformation of stablecoin reserves from cash to Treasury instruments created a straightforward yet highly lucrative business model: capture the spread between the near-zero interest rate paid to stablecoin holders and the risk-free rate on government securities. Understanding exactly how this yield generation works requires examining the specific instruments and market operations that stablecoin issuers employ.

Treasury Bill Purchases represent the most direct approach. A Treasury bill is a short-term debt obligation issued by the U.S. government with maturities ranging from a few days to 52 weeks. Unlike bonds, bills are sold at a discount to their face value and do not pay periodic interest. Instead, investors earn returns through the difference between the purchase price and the par value received at maturity. For example, if a 3-month Treasury bill with a $1,000 face value sells for $987.50, the buyer earns $12.50 in yield over three months, equivalent to approximately 5% annualized.

Stablecoin issuers can purchase Treasury bills directly through primary dealers or on secondary markets. When Circle holds $28 billion in Treasury securities, those positions represent outright purchases of bills across various maturities, typically weighted toward shorter dates to maintain liquidity. The yield on these positions flows directly to Circle's bottom line, since USDC holders receive no interest on their holdings.

In a 5% rate environment, $28 billion in Treasury bills generates approximately $1.4 billion in annual gross interest income. After deducting operational costs, regulatory compliance expenses, and redemption-related transactions, the net margin remains substantial. This explains why stablecoin issuance became such an attractive business once interest rates rose from near-zero levels in 2022-2023.

Reverse Repurchase Agreements offer an alternative mechanism, particularly for overnight positions. In a reverse repo transaction, the stablecoin issuer effectively lends cash to a counterparty (typically a primary dealer or the Federal Reserve itself) in exchange for Treasury securities as collateral. The transaction includes an agreement to reverse the trade the next day at a slightly higher price, with the price differential representing the interest earned.

The Federal Reserve's overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRP) became particularly important for stablecoin issuers. This facility allows eligible counterparties to deposit cash with the Fed overnight and receive interest at the overnight reverse repo rate, with Treasury securities provided as collateral. While stablecoin issuers cannot access the ON RRP directly (eligibility is limited to banks, government-sponsored enterprises, and money market funds), they can access it indirectly by investing in government money market funds that participate in the facility.

The advantage of reverse repo is perfect liquidity: these are genuinely overnight positions that can be unwound daily to meet redemption demands. The disadvantage is that overnight rates are typically lower than rates on term bills. Issuers therefore maintain a mix, using reverse repo for their liquidity buffer while investing the remainder in term Treasury bills to capture higher yields.

Money Market Funds serve as another vehicle for Treasury exposure, particularly Treasury-only government money market funds. These funds invest exclusively in Treasury securities and related repurchase agreements. They offer professional management, diversification across maturities, and typically maintain a stable $1.00 net asset value, making them functionally equivalent to cash for liquidity purposes while generating yield.

Circle has explicitly structured part of its reserve holdings through the Circle Reserve Fund, managed by BlackRock. This fund invests exclusively in cash, U.S. Treasury obligations, and repurchase agreements secured by U.S. Treasuries (Circle Reserve Fund documentation). By utilizing an institutional money market fund, Circle gains several advantages: professional portfolio management, economies of scale in transaction costs, automatic diversification across maturities and instruments, and enhanced liquidity management through same-day redemption features.

The mechanics work as follows: Circle deposits a portion of USDC reserves into the Reserve Fund, receives shares valued at $1.00 each, and earns a yield that fluctuates with overnight and short-term Treasury rates. The fund manager handles all securities purchases, maturities, and rollovers. When Circle needs cash for USDC redemptions, it redeems fund shares on a same-day basis, converting them back to cash. This arrangement allows Circle to maintain the liquidity characteristics of a cash deposit while earning Treasury-like yields.

Tri-Party Repurchase Agreements add another layer of sophistication. In a tri-party repo, a third-party custodian (typically a clearing bank like Bank of New York Mellon or JPMorgan Chase) sits between the cash lender and the securities borrower, handling collateral management, margin calculations, and settlement. This reduces operational burden and counterparty risk for both parties.

For stablecoin issuers, tri-party repo arrangements allow them to lend cash against high-quality Treasury collateral with daily mark-to-market margining and automated collateral substitution. If a counterparty faces financial stress, the custodian can liquidate the Treasury collateral and return cash to the lender. These arrangements typically offer higher yields than ON RRP while maintaining strong liquidity and safety characteristics.

Securities Lending represents a more advanced strategy that some larger issuers may employ. In a securities lending arrangement, an entity that owns Treasury securities lends them to other market participants (typically broker-dealers or hedge funds seeking to short Treasuries or meet delivery obligations) in exchange for a lending fee. The borrower posts collateral, usually cash or other securities, worth slightly more than the lent securities.

For a stablecoin issuer, this creates a double yield opportunity: earn interest on the Treasury securities themselves, plus earn lending fees by making those securities available to the lending market. However, securities lending introduces additional operational complexity and counterparty risk. If a borrower defaults and the collateral is insufficient to replace the lent securities, the lender faces losses. Most stablecoin issuers have avoided securities lending given the reputational risks and regulatory scrutiny, though it remains theoretically possible.

Treasury ETFs and Overnight Vehicles provide additional options for reserve deployment. Short-term Treasury ETFs like SGOV (iShares 0-3 Month Treasury Bond ETF) or BIL (SPDR Bloomberg 1-3 Month T-Bill ETF) offer instant liquidity through exchange trading while maintaining Treasury exposure. An issuer could theoretically hold these ETFs in a brokerage account and sell shares during market hours to meet redemption demands, though most prefer direct Treasury holdings or money market funds due to the potential for ETF prices to trade at small premiums or discounts to net asset value.

The Flow of Funds in practice follows a clear path:

- A user deposits $1 million with an authorized Circle partner or directly with Circle through banking channels

- Circle mints 1 million USDC tokens and delivers them to the user's wallet

- Circle receives $1 million in cash in its operating accounts

- Circle's treasury operations team immediately deploys this cash into the reserve fund: perhaps $100,000 stays in overnight reverse repo for immediate liquidity, while $900,000 purchases Treasury bills maturing in 1-3 months

- Those Treasury positions generate yield - perhaps $45,000 annually at 5% rates

- When the user later wants to redeem, they return 1 million USDC tokens to Circle

- Circle destroys (burns) the tokens and returns $1 million to the user

- To fund this redemption, Circle either uses its cash buffer or sells Treasury bills on secondary markets, receiving same-day or next-day settlement

The user receives exactly $1 million back - no interest, no fees (beyond any fees charged by intermediaries). Circle keeps the entire $45,000 in interest income generated during the period the capital was deployed. This is the fundamental economics of the fiat-backed stablecoin model in a positive interest rate environment.

Yield Striping and Maturity Laddering optimize this process. Stablecoin issuers don't simply dump all reserves into a single Treasury bill maturity. Instead, they construct laddered portfolios with staggered maturities: perhaps 20% in overnight positions, 30% in 1-week to 1-month bills, 30% in 1-3 month bills, and 20% in 3-6 month bills. This laddering ensures that some positions mature weekly, providing regular liquidity without requiring asset sales. It also allows issuers to capture higher yields on the term portion of the curve while maintaining sufficient overnight liquidity.

The practical result is that major stablecoin issuers have become sophisticated fixed-income portfolio managers, operating treasury desks that would be familiar to any corporate treasurer or money market fund manager. They monitor yield curves, execute rollovers as bills mature, manage settlement timing, maintain relationships with primary dealers, and optimize the tradeoff between yield and liquidity on a continuous basis.

This infrastructure represents a profound shift from crypto's early ethos of decentralization and disintermediation. The largest "decentralized" finance protocols now depend on centralized entities operating traditional fixed-income portfolios denominated in U.S. government debt. The returns from this model have proven too compelling to resist.

Who Earns What: The Economics

The revenue model behind Treasury-backed stablecoins is deceptively simple: issuers capture nearly all the yield generated by reserves, while users receive a stable claim on dollars with zero or minimal interest. However, the full economics involve multiple parties extracting value at different points in the chain, and understanding these splits is crucial to grasping the incentive structure driving the sector's growth.

Issuer Margins constitute the largest share of economic rent. Consider Circle as a worked example. With approximately $28 billion in USDC reserves deployed predominantly in Treasury securities and reverse repo agreements as of mid-2024, and with short-term rates averaging around 5% in that environment, Circle's gross interest income would approximate $1.4 billion annually. Against this, Circle faces several categories of costs.

Operational expenses include technology infrastructure to maintain the blockchain integrations across multiple networks (Ethereum, Solana, Arbitrum, and others), staff costs for engineering and treasury operations, and customer support for authorized partners and large clients. Regulatory and compliance costs have grown substantially, encompassing legal expenses, attestation fees paid to accounting firms, licenses and regulatory registrations in multiple jurisdictions, and ongoing compliance monitoring. Banking relationship costs include fees paid to custodian banks, transaction costs for deposits and redemptions, and account maintenance fees at multiple banking partners to maintain operational resilience.

Redemption-related costs occur when users convert USDC back to dollars. While many redemptions can be met from incoming issuance flows, significant net outflows require selling Treasury securities before maturity. This triggers bid-ask spreads in secondary markets and potential mark-to-market losses if interest rates have risen since purchase. During the March 2023 banking crisis when USDC experienced approximately $10 billion in redemptions over several days, Circle had to liquidate substantial Treasury positions, likely incurring millions in trading costs and market impact.

Industry analyst estimates suggest that well-run stablecoin issuers operating at scale achieve net profit margins in the range of 70-80% on interest income during elevated rate environments (Messari Research, "The Stablecoin Economics Report," 2024). Applying this to Circle's $1.4 billion in gross interest would imply net profits approaching $1 billion annually - a remarkable return for what is essentially a money market fund with a fixed $1.00 share price that never pays distributions to shareholders.

Tether's economics are even more striking due to its larger scale. With approximately $120 billion in circulation and similar reserve composition, Tether would generate roughly $6 billion in annual gross interest income in a 5% rate environment. Tether has historically disclosed less detailed expense information, but its profit attestations have confirmed extraordinary profitability. In its Q1 2024 attestation, Tether reported $4.5 billion in excess reserves (assets beyond the 1:1 backing requirement) accumulated from years of retained earnings (Tether Transparency Report, Q1 2024). This excess represents years of yield capture flowing to the company's bottom line rather than to token holders.

Returns to Holders are explicitly zero for traditional stablecoins like USDC and USDT. This is a feature, not a bug, of the business model. Issuers have strongly resisted adding native yield to their tokens for several reasons. Paying interest would make stablecoins more obviously securities under U.S. law, triggering full SEC regulation and registration requirements. It would reduce the enormous profit margins that make the business attractive to operators and investors. And it would complicate the use cases; stablecoins function as transaction media and numeraires precisely because their value is stable and simple - adding variable interest rates would introduce complexity.

However, a category of yield-bearing stablecoins has emerged to capture the opportunity issuers were leaving on the table. These tokens either distribute yield generated by reserves to holders or appreciate in value over time relative to dollars. Examples include:

sUSDe (Ethena's staked USDe) distributes yield from Ethena's Delta-neutral perpetual futures strategy and Treasury holdings to stakers, with annual percentage yields that have ranged from 8-27% depending on funding rates and Treasury exposures.

sFRAX (Frax's staked version) accumulates yield from Frax Protocol's automated market operations and RWA holdings.

Mountain Protocol's USDM passes through Treasury yields to holders after fees, effectively operating as a tokenized Treasury money market fund with explicit yield distribution.

The economics of these yield-bearing variants differ fundamentally. By distributing yield, they sacrifice the issuer's ability to capture the full spread, but they gain competitive advantages in attracting capital and DeFi integrations. Whether yield-bearing stablecoins can achieve the scale of zero-yield alternatives remains an open question, but their existence demonstrates market demand for returns on dollar-denominated crypto holdings.

Custodian and Banking Fees extract another layer of value. Stablecoin issuers must maintain relationships with qualified custodians - typically large banks with trust charters or specialized digital asset custodians regulated as trust companies. These custodians charge fees for holding assets, processing transactions, providing attestation support, and maintaining segregated accounts.

Custodian fee structures vary but typically include basis point fees on assets under custody (perhaps 2-5 basis points annually on Treasury holdings), per-transaction fees for deposits and withdrawals, and monthly account maintenance fees. For a $28 billion reserve portfolio, even modest 3 basis point fees amount to $8.4 million annually. These costs are material in absolute terms though small relative to the issuer's yield capture.

Banking partners also charge fees for operating the fiat on-ramps and off-ramps. When a user deposits dollars to mint stablecoins, that transaction typically flows through a bank account, triggering wire fees or ACH costs. Redemptions trigger similar charges. For retail users, intermediaries may charge additional spreads or fees beyond what the issuer charges.

Market Maker Profits emerge in the secondary market for stablecoins. While stablecoins theoretically trade at $1.00, actual trading prices fluctuate based on supply and demand across decentralized exchanges. Market makers profit from these spreads by providing liquidity on DEXs and CEXs, buying below $1.00 and selling above, or arbitraging price differences across venues.

During periods of stress, these spreads widen significantly. In March 2023 when USDC briefly depegged to $0.87 due to Silicon Valley Bank exposure concerns, sophisticated traders who understood the situation bought USDC at a discount and redeemed directly with Circle at par, earning instant 15% returns (though bearing the risk that Circle might not honor redemptions at par if banking problems worsened). These arbitrage opportunities are self-limiting; they attract capital that pushes prices back toward peg.

Protocol and DAO Treasury Revenue accrues to DeFi protocols that integrate stablecoins into their operations. When stablecoins are deposited into lending protocols like Aave or Compound, these protocols earn spreads between borrowing and lending rates. When stablecoins are used to mint other synthetic assets or provide liquidity in automated market makers, fees flow to liquidity providers and protocol treasuries.

Some protocols have begun to recognize that holding large stablecoin reserves in their treasuries means forgoing substantial yield. This has driven interest in tokenized Treasury products that allow DAOs to earn yield on dollar-denominated holdings while maintaining on-chain composability. MakerDAO's move to integrate over $1 billion in tokenized Treasury exposure into DAI's backing represents one manifestation of this trend (Spark Protocol documentation, 2024).

Investor Returns flow to the venture capital and equity investors backing stablecoin issuers. Circle raised over $1 billion from investors including Fidelity, BlackRock, and others before filing for a public offering. These investors will realize returns through eventual liquidity events, with valuations based on the recurring revenue streams from reserve management. At a 70% net margin on $1.4 billion in annual revenue, Circle's stablecoin operations could generate $1 billion in annual net income, potentially supporting a multi-billion dollar valuation.

The overall economics reveal a highly concentrated value capture model. The issuer retains the vast majority of economic surplus (perhaps 70-80% of gross yield), custodians and market makers capture small percentages, and the end users who deposit the capital receive nothing beyond the utility of holding stable dollars on blockchain rails. This distribution may prove unstable over time as competition increases and users demand yield, but in the current market structure, it remains remarkably persistent.

What makes this model particularly attractive is its scalability and capital efficiency. Once the infrastructure is built, incremental USDC or USDT issuance requires minimal additional cost but generates linear increases in interest income. A stablecoin issuer at $50 billion scale has few advantages in treasury management over one at $150 billion scale, suggesting that competition will concentrate around a handful of dominant players who can leverage their scale advantages in regulatory compliance, banking relationships, and network effects.

The consequence is an industry structure that resembles money market funds but with dramatically different economics. Traditional money market funds operate on extremely thin margins, competing for assets by maximizing yields passed to investors. Stablecoin issuers capture orders of magnitude more profit per dollar of assets because they do not compete on yield. This dislocation cannot persist indefinitely as the market matures, but for now, it represents one of the most profitable business models in finance.

On-Chain and Off-Chain Convergence: Tokenized T-Bills, RWAs, and DeFi

The evolution of stablecoins from pure cash reserves to Treasury-backed instruments represents the first phase of crypto's integration with government debt markets. The emergence of tokenized Treasury products and real-world asset (RWA) protocols represents the second phase - one that promises to deepen these linkages while creating new forms of composability and systemic connectivity.

Tokenized Treasury Bills bring U.S. government debt directly onto blockchain networks, creating native crypto assets that represent ownership of specific Treasury securities. Unlike stablecoins, which aggregate reserves and promise redemption at par, tokenized Treasuries represent direct fractional ownership of underlying securities, similar to how securities are held in brokerage accounts.

Several models have emerged for Treasury tokenization. The first approach involves custodial wrappers where a regulated entity purchases Treasury bills, holds them in custody, and issues blockchain tokens representing beneficial ownership. Examples include:

Franklin Templeton's BENJI (launched on Stellar and Polygon) allows investors to purchase tokens representing shares in the Franklin OnChain U.S. Government Money Fund. Each token represents a proportional claim on a portfolio of Treasury securities and government repo agreements, with the fund operating under traditional money market fund regulations but with blockchain-based share registration and transfer capabilities.

Ondo Finance's OUSG provides exposure to short-term Treasury securities through a tokenized fund structure. Ondo partners with traditional fund administrators and custodians to hold the underlying securities while issuing ERC-20 tokens on Ethereum that represent fund shares. The fund pursues a short-duration Treasury strategy similar to money market funds, allowing holders to earn Treasury-like yields with the convenience of on-chain holdings.

Backed Finance's bIB01 tokenizes a BlackRock Treasury ETF, creating a synthetic representation that tracks short-duration Treasury exposure. By wrapping existing ETF shares rather than directly holding securities, this approach reduces regulatory complexity while providing crypto-native access to government debt yields.

MatrixDock's STBT (Short-Term Treasury Bill Token) represents direct ownership of Treasury bills held by regulated custodians. Investors can purchase STBT tokens using stablecoins or fiat, and the tokens accrue value based on the underlying Treasury yields. This model aims to provide something closer to direct securities ownership rather than fund shares.

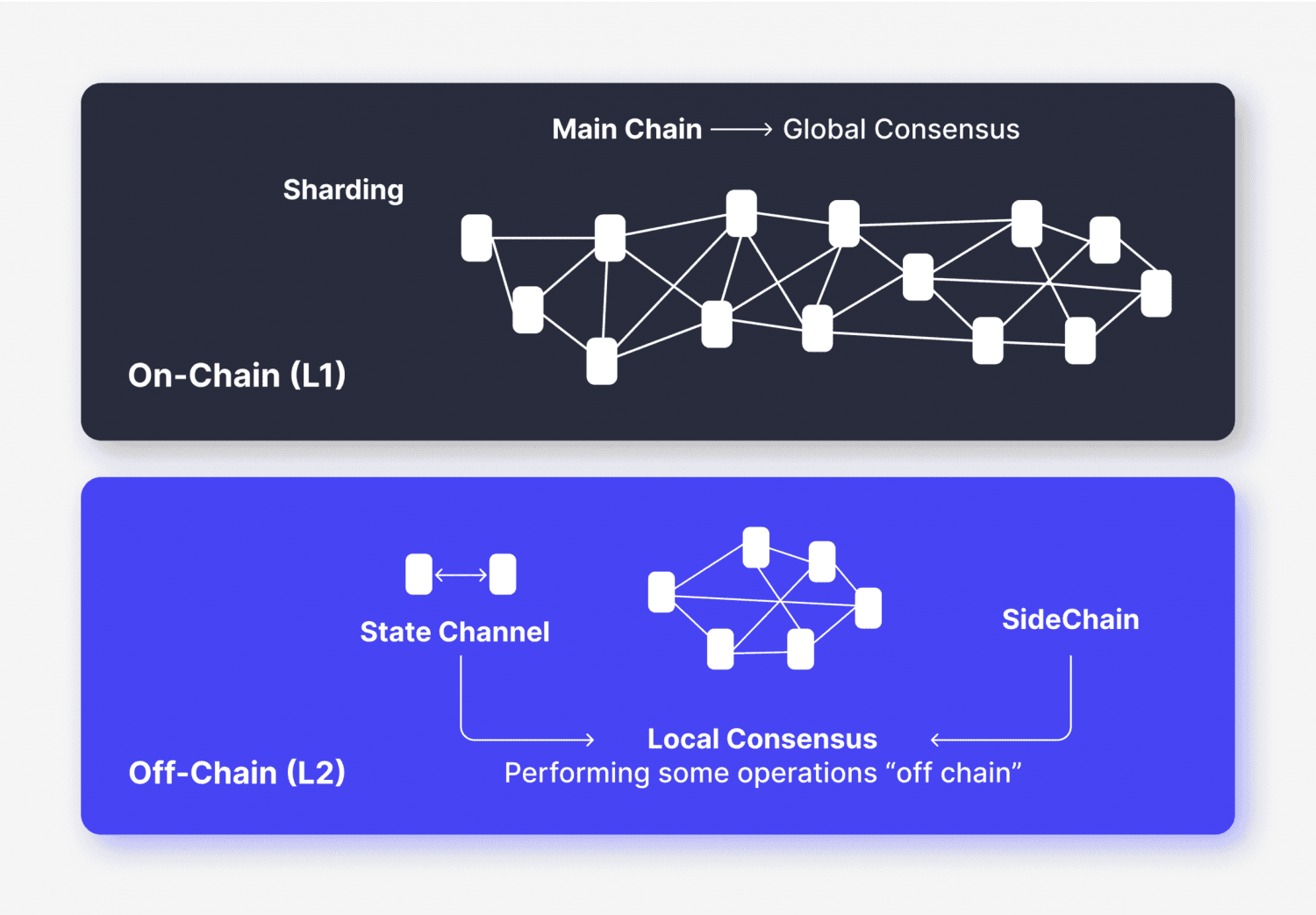

The technical mechanics involve several layers. At the base sits the actual Treasury security, purchased and held by a regulated custodian or fund manager. A smart contract layer mints tokens representing ownership interests in these securities. Transfer restrictions and KYC/AML checks are typically implemented either through permissioned blockchains, token whitelisting, or on-chain identity verification protocols. Value accrual mechanisms vary; some tokens increase in value over time (like Treasury bills themselves), while others pay periodic distributions to holders.

The legal structures also vary significantly. Some tokenized products operate as registered investment funds under traditional securities law, others as private placement offerings limited to accredited investors, and still others as regulated trust products where tokens represent beneficial interests. This legal diversity creates challenges for DeFi integration and cross-border use, since different structures face different restrictions on transferability and eligible holders.

DeFi Integration is where tokenized Treasuries become truly consequential. Traditional stablecoins operate as separate assets from DeFi protocols; USDC on Aave is lent and borrowed, but the underlying Treasury reserves remain locked in Circle's custodial accounts, not composable with other protocols. Tokenized Treasuries, by contrast, can potentially serve as collateral in lending protocols, provide liquidity in decentralized exchanges, back synthetic assets, and integrate into more complex financial primitives.

MakerDAO's integration of RWA vaults exemplifies this convergence. In 2023-2024, MakerDAO (now operating under the Sky brand) progressively increased its exposure to tokenized real-world assets, particularly short-term Treasury exposure through partners like BlockTower and Monetalis. These RWA vaults allow MakerDAO to deploy DAI treasury holdings into yield-generating off-chain assets, with the returns helping to maintain DAI's peg and fund DAO operations. The mechanism works through legal structures where specialized entities purchase Treasuries using capital borrowed from MakerDAO in exchange for collateral and payment of interest.

Ethena Labs' USDe demonstrates another integration model. USDe maintains its dollar peg through Delta-neutral perpetual futures positions (being long spot crypto and short an equivalent amount of perpetual futures contracts) which generate yield from funding rate payments. However, when funding rates turn negative (meaning shorts pay longs), this strategy becomes yield-negative. To address this, Ethena allocates a portion of its backing to Treasury bills during such periods, effectively toggling between on-chain derivatives yield and off-chain Treasury yield based on market conditions (Ethena documentation). This dynamic allocation would be difficult to implement without tokenized or easily accessible Treasury products.

Frax Finance has pursued a more aggressive RWA strategy through its Frax Bond system (FXB), which aims to create on-chain representations of various maturity Treasury bonds. The goal is to build a yield curve of tokenized Treasuries on-chain, allowing DeFi protocols to access not just short-term money market rates but also longer-duration government yields. This would enable more sophisticated fixed-income strategies in DeFi, though implementation has faced regulatory and technical challenges.

Aave Arc and Permissioned DeFi Pools represent another convergence point. Recognizing that regulated institutional investors cannot interact with fully permissionless protocols, Aave launched Arc (and later, Aave institutions-focused initiatives) to create whitelisted pools where only KYC-verified participants can lend and borrow. Tokenized Treasuries can potentially serve as collateral in such pools, allowing institutions to gain leverage against government securities holdings while remaining within regulatory boundaries. This creates a bridge between traditional finance and DeFi, mediated by tokenized Treasury products.

The legal and technical differences between custodied Treasuries backing stablecoins and tokenized Treasuries are substantial. When Circle holds $28 billion in Treasuries backing USDC, those securities exist as conventional holdings at custodian banks, registered in Circle's name or in trust for USDC holders. They are not divisible, not directly transferable on-chain, and not usable as collateral outside of Circle's own operations. USDC holders have a contractual claim to redemption at par, but no direct property interest in the underlying Treasuries.

Tokenized Treasuries, by contrast, represent direct or fund-level ownership interests. A holder of Franklin's BENJI tokens owns a fractional share of the underlying fund's portfolio, similar to owning shares of a conventional money market fund. This ownership interest may be transferable (subject to securities law restrictions), usable as collateral in other protocols, and potentially redeemable directly for underlying securities rather than just cash.

These differences create distinct risk profiles and use cases. Stablecoins remain superior for payment and transaction use cases because they maintain stable $1.00 pricing and avoid mark-to-market fluctuations. Tokenized Treasuries may fluctuate slightly in value based on interest rate movements and accrued interest, making them less ideal as payment media but more suitable as collateral or investment vehicles. The two categories are complementary rather than competitive.

Regulatory Implications of tokenization remain unclear in many jurisdictions. In the United States, tokenized Treasuries that represent fund shares are likely securities requiring registration or exemption under the Investment Company Act and Securities Act. The SEC has provided limited guidance on how to structure these products compliantly, creating legal uncertainty that has slowed institutional adoption. In Europe, the Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation will classify most tokenized Treasuries as asset-referenced tokens requiring authorization and reserve management similar to stablecoins, though with different requirements if they qualify as securities.

The broader trend is unmistakable: crypto is building an increasingly sophisticated infrastructure for representing and transacting in U.S. government debt. What began as stablecoin issuers parking reserves in Treasuries has evolved into multiple parallel efforts to bring Treasuries directly on-chain, integrate them into DeFi protocols, and create yield curves and term structures that mirror traditional fixed-income markets.

The end state may be a parallel financial system where most dollar-denominated assets on-chain ultimately trace back to Treasury exposure, creating deep dependencies between crypto market functioning and U.S. government debt market stability.

How Stablecoin Flows Influence Fed Operations and the Treasury Market

The scale of stablecoin reserve deployment into Treasury markets has grown large enough to create measurable effects on interest rates, repo market dynamics, and Federal Reserve policy transmission. Understanding these feedback loops is critical to assessing both the financial stability implications and the potential for regulatory intervention.

Size and Scale in Context: As of mid-2024, the combined market capitalization of major fiat-backed stablecoins exceeded $150 billion, with approximately $120-130 billion held in U.S. Treasury bills and related money market instruments based on disclosed reserve compositions (aggregated from Circle, Tether, and other issuer reports). To put this in perspective, $130 billion represents roughly 2-3% of the total outstanding U.S. Treasury bill market, which stood at approximately $5.5 trillion as of Q2 2024. While not dominant, this is large enough to matter, particularly during periods of rapid inflows or outflows.

For comparison, $130 billion is larger than the Treasury holdings of many sovereign wealth funds, exceeds the foreign exchange reserves of numerous countries, and approaches the size of major money market fund complexes. When stablecoin net issuance grows by $40-50 billion over a few months, as occurred in early 2024, that capital flow represents demand for short-term Treasuries comparable to what a mid-sized central bank might generate over the same period.

Demand Effects on Treasury Yields: When stablecoin issuance accelerates, issuers must deploy billions in newly minted dollars into Treasury bills and repo agreements within days or weeks to earn yields and maintain reserve adequacy. This surge in demand for short-dated securities compresses yields, all else equal. The mechanism is straightforward: increased buying pressure for a fixed supply of bills pushes prices up and yields down.

The effect is most pronounced at the very short end of the curve, particularly for overnight and one-week maturities where stablecoin issuers maintain their highest liquidity buffers. During periods of strong stablecoin growth in 2023-2024, observers noted persistent downward pressure on overnight repo rates and Treasury bill yields at the shortest maturities, even as the Federal Reserve maintained policy rates around 5.25-5.5%. While multiple factors influence these rates, stablecoin demand contributed to the compression.

This creates a paradox: stablecoins are most profitable for issuers when interest rates are high, but their success in attracting deposits and growing issuance tends to push the rates they can earn on those deposits downward through demand effects. This feedback loop is self-limiting but creates interesting dynamics in rate-setting markets.

Repo Market Interactions: The overnight and term repo markets serve as the plumbing of the U.S. financial system, allowing banks, hedge funds, and other institutions to borrow cash against Treasury collateral or vice versa. The Federal Reserve's reverse repo facility (where counterparties lend cash to the Fed overnight) and repo facility (where the Fed lends cash against collateral) establish floor and ceiling rates that influence the entire money market structure.

Stablecoin issuers' reliance on repo agreements as reserve instruments integrates them directly into this system. When Circle or Tether invest billions in overnight reverse repo, they are effectively supplying cash to repo markets that would otherwise be supplied by money market funds or other cash-rich institutions. This tends to put upward pressure on repo rates (since more cash is being lent) all else equal, though the effect is muted by the Fed's ON RRP facility which provides an elastic supply of counterparty capacity at a fixed rate.

The more significant impact occurs during stress events. If stablecoins experience rapid redemptions, issuers must extract billions from repo markets over short periods, creating sudden demand for cash and reducing the cash available to other repo market participants.

During the March 2023 USDC depeg event, when approximately $10 billion in redemptions occurred over three days, Circle liquidated substantial repo and Treasury positions to meet redemptions. This type of forced selling can amplify volatility in repo markets during precisely the moments when liquidity is most valuable.

Federal Reserve Policy Transmission: The Fed's policy rate decisions affect stablecoin economics and hence stablecoin issuance, creating feedback into Treasury markets. When the Fed raises rates, the profit margin for stablecoin issuers increases (they earn more on reserves while still paying zero to holders), making stablecoin issuance more attractive to operators and potentially spurring growth. This growth increases demand for short-term Treasuries, partially offsetting the Fed's tightening intent by keeping yields compressed at the short end.

Conversely, if the Fed cuts rates toward zero, stablecoin economics deteriorate dramatically. In a near-zero rate environment, issuers earn minimal yields on Treasury reserves, making the business model far less attractive (though still valuable for payment services). This could slow stablecoin growth or even trigger redemptions as issuers reduce capacity or users seek better yields elsewhere. Reduced stablecoin demand for Treasuries would remove a source of demand from bill markets.

This creates a pro-cyclical dynamic: stablecoin demand for Treasuries is highest when rates are high (when the Fed is tightening) and lowest when rates are low (when the Fed is easing). This pattern tends to work against the Fed's monetary policy intentions, providing unintended support for Treasury prices during tightening cycles and withdrawing support during easing cycles.

Market Structure and Concentration Risks: The concentration of stablecoin reserves among a handful of issuers, invested through a small number of custodian relationships, creates potential points of fragility. If Tether, with $120 billion under management, needed to liquidate substantial Treasury positions rapidly, that volume would affect market depth and pricing. During the 2008 financial crisis, forced selling by money market funds facing redemptions amplified Treasury market volatility; stablecoins could play a similar role in future stress scenarios.

The concentration is also evident in custodial relationships. Most stablecoin reserves are held through just a few large custodian banks and institutional trust companies. If one of these custodians faces operational problems or regulatory restrictions, it could impair multiple stablecoin issuers' ability to access reserves, triggering redemption bottlenecks. The March 2023 Silicon Valley Bank failure, which held substantial Circle deposits, illustrated this interconnection risk. While only a small portion of USDC reserves were affected, the uncertainty triggered a depeg and $10 billion in redemptions.

Volatility Amplification During Crypto Market Stress: Stablecoin redemption dynamics are closely tied to crypto market cycles. When crypto prices fall sharply, traders flee to stablecoins, increasing issuance. When they recover, traders redeem stablecoins to buy crypto, reducing issuance. When confidence breaks entirely, users may exit crypto completely, redeeming stablecoins for fiat and removing billions from the system.

These cyclical flows create corresponding volatility in Treasury demand. A $50 billion reduction in stablecoin supply over several months translates to $50 billion in Treasury selling, occurring during periods when crypto markets are likely already experiencing stress. If crypto stress coincides with broader financial stress, this forced Treasury selling would occur when market liquidity is most challenged, potentially amplifying problems.

The converse is also true: during crypto bull markets when stablecoin issuance surges, tens of billions in new Treasury demand emerges from a non-traditional source, potentially distorting price signals and rate structures in ways that confuse policymakers trying to read market sentiment.

Cross-Border Capital Flows: Unlike traditional money market funds which primarily serve domestic investors, stablecoins are global by nature. A user in Argentina, Turkey, or Nigeria can hold USDT or USDC as a dollar substitute, effectively accessing U.S. Treasury exposure without directly interacting with U.S. financial institutions. This creates channels for capital flow that bypass traditional banking surveillance and balance of payments statistics.

When global users accumulate billions in stablecoins, they are indirectly accumulating claims on U.S. Treasury securities, funded by capital outflows from their home countries. This demand for dollar-denominated stores of value supports both the dollar and Treasury markets, but it occurs outside formal channels that central banks and regulators traditionally monitor. During currency crises or capital control periods, stablecoin adoption can accelerate, creating sudden spikes in demand for Treasuries that market participants may struggle to explain using conventional models.

The integration of stablecoins into monetary plumbing is still in early stages, but the direction is clear: crypto has created a new channel for transmitting monetary policy, distributing government debt, and mobilizing global dollar demand, with feedback effects that central banks and treasury departments are only beginning to study systematically.

Risks: Concentration, Runs, and Maturity Transformation

The fusion of stablecoin infrastructure and Treasury exposure creates multiple categories of risk, some familiar from traditional money markets and others unique to crypto-native systems. Understanding these risks is essential because a major stablecoin failure could have ripple effects extending far beyond crypto markets.

Run Dynamics and Redemption Spirals represent the most immediate danger. Stablecoins promise instant or near-instant redemption at par, but their reserves are invested in securities that may take days to liquidate at full value. This maturity mismatch creates classic run vulnerability: if a large percentage of holders simultaneously attempt to redeem, the issuer may be forced to sell Treasury securities into falling markets, realize losses, and potentially break the peg.

The mechanism differs from bank runs in important ways. Banks face legal restrictions on how quickly they can be drained; wire transfers and withdrawal limits impose friction. Stablecoins can be transferred instantly and globally, 24/7, with no practical limits beyond blockchain congestion. A loss of confidence can trigger redemptions at digital speed. During the March 2023 USDC event, approximately $10 billion redeemed in roughly 48 hours - a burn rate that would challenge any reserve manager.

The TerraUSD collapse in May 2022 demonstrated how quickly confidence can evaporate in crypto markets. UST lost its peg over a few days, triggering a death spiral where redemptions begat price declines which begat more redemptions. While fiat-backed stablecoins have stronger backing than algorithmic stablecoins, they are not immune to similar dynamics if doubt emerges about reserve adequacy or liquidity.

The structure of stablecoin redemptions creates additional pressure. Typically, only large holders and authorized participants can redeem directly with issuers, while smaller holders must sell on exchanges. During stress events, exchange liquidity can dry up, causing stablecoins to trade at discounts to par even while direct redemptions remain available. This two-tiered structure means retail holders may experience losses even if institutional holders can redeem at par, creating distributional inequities and accelerating panic.

Liquidity Mismatch arises from the fundamental tension between instant redemption promises and day-to-day settlement cycles in Treasury markets. While Treasury bills are highly liquid, executing large sales and receiving cash still requires interaction with dealer markets and settlement systems that operate on business-day schedules. If redemptions spike on a weekend or during market closures, issuers may face hours or days during which they cannot fully access reserves to meet outflows.

Stablecoin issuers manage this through liquidity buffers - portions of reserves held in overnight instruments or cash. However, determining the right buffer size involves guesswork about tail-risk redemption scenarios. Too small a buffer leaves the issuer vulnerable; too large a buffer sacrifices yield. The March 2023 USDC event suggested that even sizable buffers may prove insufficient during confidence crises.

Mark-to-Market vs. Amortized Cost Accounting creates transparency and valuation challenges. Treasury bills held to maturity return par value regardless of interim price fluctuations, but bills sold before maturity realize market prices. If interest rates rise after an issuer purchases bills, those bills decline in market value, creating unrealized losses.

Stablecoin attestation reports typically value reserves using amortized cost or fair value approaches. Amortized cost assumes bills will be held to maturity and values them based on purchase price adjusted for accruing interest. Fair value marks positions to current market prices. In stable conditions, these methods produce similar results, but during interest rate volatility, gaps can emerge.

If an issuer holds $30 billion in Treasury bills at amortized cost but interest rates have risen such that the fair value is only $29.5 billion, which number represents the "true" reserve value? If forced selling occurs, only $29.5 billion may be realizable, creating a $500 million gap. Some critics argue that stablecoins should mark all reserves to market value and maintain over-collateralization buffers to absorb such gaps, but most issuers use cost-basis accounting and claim 1:1 backing without additional buffers.

Counterparty and Custodial Concentration poses operational risks. Stablecoin reserves are held at a small number of banking and custody institutions. If one of these institutions faces regulatory intervention, technological failure, or bankruptcy, access to reserves could be impaired. The Silicon Valley Bank failure in March 2023 demonstrated this risk; USDC's exposure was only about 8% of reserves, but even that limited exposure triggered sufficient uncertainty to cause a temporary depeg.

More broadly, the crypto custody industry remains young and evolving. Operational risks include cyber attacks on custodian systems, internal fraud, technical failures that impair access to funds, and legal complications in bankruptcy or resolution scenarios. While traditional custody banks have decades of institutional experience, the crypto custody space includes newer entrants with shorter track records.

Regulatory and Jurisdictional Arbitrage creates risks from inconsistent oversight. Stablecoin issuers are chartered in various jurisdictions with different regulatory approaches. Circle operates as a money transmitter in the U.S. with varying state-level licenses. Tether is registered in the British Virgin Islands with less stringent disclosure requirements. Paxos operates as a New York trust company with strong regulatory oversight. This patchwork means that similar products face different rules, disclosure standards, and supervisory intensity.

The potential for regulatory arbitrage is obvious: issuers may locate in jurisdictions with lighter oversight while serving global users, externalizing risks to the broader system. If a crisis emerges, the lack of clear regulatory authority and resolution frameworks could create coordination problems and delay effective responses.

Contagion Channels to Traditional Finance run in both directions. If a major stablecoin fails, forced liquidation of billions in Treasuries could disrupt repo markets and money market funds, particularly if the liquidation occurs during a period of broader market stress. The selling would affect prices and liquidity, creating mark-to-market losses for other Treasury holders and potentially triggering margin calls and additional forced selling.

Conversely, stress in traditional finance can contaminate stablecoins. Banking system problems can impair stablecoin issuers' access to custodied reserves, as occurred with Silicon Valley Bank. A broader banking crisis could create cascading failures across multiple stablecoin custodians simultaneously. Money market fund problems could impair the funds that some stablecoin issuers use for reserve management.

Historical Analogies provide sobering context. The Reserve Primary Fund "broke the buck" in September 2008 when its holdings of Lehman Brothers commercial paper became worthless, triggering redemptions across the entire money market fund industry. The Fed ultimately intervened with lending programs to stabilize the sector, but not before significant damage occurred.

Earlier, in the 1970s, money market funds experienced periodic runs as investors questioned the value of underlying commercial paper holdings during corporate debt crises. These events led to regulatory reforms including stricter portfolio rules, disclosure requirements, and eventual SEC oversight under the Investment Company Act.

Stablecoins today resemble money market funds circa 1978: rapidly growing, lightly regulated, increasingly systemic, and operating under voluntary industry standards rather than comprehensive regulatory frameworks. The question is whether stablecoins will experience their own "breaking the buck" moment before regulation catches up, or whether proactive regulatory intervention can avert such an event.

Maturity Transformation and Credit Intermediation creates additional concerns if stablecoins evolve toward lending practices. Currently, most major stablecoins invest only in government securities and repo, avoiding credit risk. However, economic incentives push toward credit extension: lending to creditworthy borrowers generates higher yields than Treasuries, increasing issuer profitability.

Some stablecoin issuers have experimented with or discussed broader reserve compositions including corporate bonds, asset-backed securities, or even loans to crypto companies. If this trend accelerates, stablecoins would begin performing bank-like credit intermediation - taking deposits (issuing stablecoins) and making loans (investing in credit products) - but without bank-like regulation, capital requirements, or deposit insurance.

This would amplify all the risks discussed above while adding credit risk: if borrowers default, reserve values decline, potentially below the value of outstanding stablecoins. Historical experience suggests that entities performing bank-like functions without bank-like regulation tend to fail catastrophically during stress events, from savings and loans in the 1980s to shadow banks in 2008.

Transparency Deficits persist despite improvements in attestation frequency and detail. Most stablecoin attestations remain point-in-time snapshots rather than continuous audits. They typically do not disclose specific counterparties, detailed maturity profiles, concentration metrics, or stress-testing results. This opacity makes it difficult for holders, market participants, and regulators to assess true risk levels.

Moreover, the attestation standards themselves vary. Some reports are true attestations by major accounting firms following established standards. Others are unaudited management disclosures. The lack of standardized, comprehensive, independently audited reporting makes comparison difficult and creates opportunities for issuers to present reserve compositions in misleading ways.

The overall risk profile suggests that while stablecoins backed primarily by short-term Treasuries are dramatically safer than algorithmic or poorly-collateralized alternatives, they are not risk-free. They remain vulnerable to runs, liquidity mismatches, operational failures, and contagion effects. The migration toward Treasury exposure reduced but did not eliminate these risks, and the growing scale of the sector increases the systemic stakes if something goes wrong.

Who Regulates What: Legal and Supervisory Gaps

The regulatory landscape for stablecoins remains fragmented across jurisdictions and unsettled within them, creating uncertainty for issuers, users, and the broader financial system. Understanding this landscape is crucial because regulatory decisions will determine whether stablecoins evolve into well-supervised components of the monetary system or remain in a gray zone vulnerable to sudden restrictions.

United States Regulatory Patchwork: No comprehensive federal framework for stablecoins existed as of late 2024, leaving issuers to navigate a complex mosaic of state, federal, and functional regulators. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has asserted that many crypto assets are securities subject to federal securities laws, but has taken inconsistent positions on whether stablecoins constitute securities. The SEC's primary concern with stablecoins relates to whether they represent investment contracts or notes under the Howey test and other securities definitions.erted that many crypto assets are securities subject to federal securities laws, but has taken inconsistent positions on whether stablecoins constitute securities. The SEC's primary concern with stablecoins relates to whether they represent investment contracts or notes under the Howey test and other securities definitions.

For yield-bearing stablecoins that promise returns to holders, the securities characterization becomes stronger. The SEC has suggested that such products likely require registration as investment companies under the Investment Company Act of 1940, subjecting them to comprehensive regulation including portfolio restrictions, disclosure requirements, and governance rules. Non-yield-bearing stablecoins like USDC and USDT occupy murkier territory; the SEC has not definitively classified them but has not exempted them either.

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) asserts jurisdiction over stablecoins to the extent they are used in derivatives markets or meet the definition of commodities. CFTC Chairman Rostin Behnam has advocated for expanded CFTC authority over spot crypto markets, which could include stablecoins used as settlement instruments on derivatives platforms.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) oversees banks and has issued guidance suggesting that national banks may issue stablecoins and provide custody services for them, but with significant restrictions and supervisory expectations. The OCC's 2021 interpretive letters indicated that banks could use stablecoins for payment activities and hold reserves for stablecoin issuers, but these positions faced subsequent uncertainty under changing OCC leadership.

State regulators maintain their own frameworks. New York's BitLicense regime regulates virtual currency businesses operating in the state, including stablecoin issuers serving New York residents. The New York Department of Financial Services requires licensees to maintain reserves equal to or exceeding outstanding stablecoin obligations, hold reserves in qualified custodians, and submit to regular examinations. Paxos operates under New York trust company charter, subjecting it to full banking-style supervision by New York regulators.

Other states have developed money transmitter licensing frameworks that may apply to stablecoin issuers. The challenge is that requirements vary dramatically: some states require reserve segregation and regular attestations, while others impose minimal standards. This creates regulatory arbitrage opportunities and uneven protection for users depending on where an issuer is located.

Federal Legislative Efforts: Multiple stablecoin bills were introduced in the U.S. Congress during 2022-2024, though none achieved passage as of late 2024. These proposals generally aimed to establish federal licensing for stablecoin issuers, impose reserve requirements, mandate regular attestations or audits, and create clear supervisory authority (either at the Fed, OCC, or a new agency).

Key provisions in various bills included requirements that reserves consist only of highly liquid, low-risk assets (typically defined as cash, Treasuries, and repo); prohibition on lending or rehypothecation of reserves; monthly public disclosure of reserve compositions; and capital or surplus requirements. Some versions would have limited stablecoin issuance to banks and federally supervised institutions, effectively prohibiting non-bank issuers like Tether from operating in the U.S. market.

The regulatory disagreements centered on whether stablecoin issuers should be treated as banks (requiring federal charters and comprehensive supervision), as money transmitters (requiring state licenses and lighter supervision), or as an entirely new category with sui generis regulation. Banking regulators generally favored stringent oversight comparable to banks, while crypto industry advocates pushed for lighter-touch frameworks that would not impose bank-level capital requirements or examination intensity.

European Union - Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA): The EU's MiCA regulation, which began taking effect in phases during 2023-2024, created the world's first comprehensive framework for crypto asset regulation, including detailed rules for stablecoins (termed "asset-referenced tokens" and "e-money tokens" under MiCA).

Under MiCA, issuers of asset-referenced tokens must be authorized by competent national authorities, maintain reserves backing tokens at least 1:1, invest reserves only in highly liquid and low-risk assets, segregate reserves from the issuer's own assets, and undergo regular audits. For e-money tokens (which reference only a single fiat currency), the requirements align more closely with existing e-money regulations in the EU, potentially allowing established e-money institutions to issue them under existing licenses with some modifications.

MiCA also imposes significant holder rights including redemption at par, disclosure obligations regarding reserve composition and valuation methodologies, and governance requirements. Perhaps most significantly, MiCA limits the ability of non-EU stablecoins to circulate in the EU unless their issuers comply with comparable regulatory standards and are authorized by EU authorities. This could theoretically restrict Tether and other non-compliant stablecoins from being offered to EU users, though enforcement mechanisms and transition timelines remain somewhat unclear.

United Kingdom Approach: The UK has pursued a hybrid approach, treating stablecoins as a distinct category of regulated tokens while building on existing e-money and payment services regulations. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and Bank of England published joint consultation papers proposing that stablecoin issuers be subject to supervision comparable to systemic payment systems, including prudential requirements, operational resilience standards, and reserve management rules.

The UK framework distinguishes between unbacked crypto assets (outside the regulatory perimeter), stablecoins used primarily for payments (subject to enhanced regulation), and stablecoins used as investment products (potentially subject to securities regulation). The Bank of England has also explored whether certain stablecoins might be designated as systemic payment systems, subjecting them to direct central bank supervision.

UK proposals generally require reserves be held in bankruptcy-remote structures, valued daily at fair value, and composed only of high-quality liquid assets. The Bank of England has indicated that for systemically important stablecoins, reserve assets should be held directly at the central bank or in forms that can be swiftly converted to central bank reserves without market risk.

International Coordination: The Financial Stability Board (FSB), Bank for International Settlements (BIS), and other international bodies have developed policy recommendations for stablecoin regulation. These recommendations generally emphasize principles including same risk, same regulation (stablecoins performing bank-like functions should face bank-like rules); comprehensive regulation of all entities in the stablecoin ecosystem (issuers, custodians, and validators); robust reserve requirements and disclosure; and regulatory cooperation across borders.

The challenge is that international standards remain non-binding recommendations unless implemented by national authorities. The variation in how jurisdictions translate these principles into domestic law creates ongoing fragmentation and regulatory arbitrage opportunities.

Disclosure and Transparency Rules: One area of relative convergence involves disclosure. Most serious regulatory proposals require monthly or quarterly public disclosure of reserve compositions with sufficient detail to allow meaningful analysis. This typically includes breakdowns by asset type, maturity profile, counterparty concentration metrics, and valuation methodologies.

However, significant differences persist in what constitutes adequate disclosure. Some jurisdictions require full audits under established accounting standards. Others accept attestations that merely confirm point-in-time existence of assets without verifying controls or continuous compliance. Still others accept unaudited management representations. These variations create confusion about which stablecoins truly meet high standards.

Resolution and Failure Frameworks: Notably absent from most regulatory regimes are clear frameworks for what happens when a stablecoin issuer fails. If Tether became insolvent, who has legal claims to the reserve assets? In what priority? Through what process? Would holders have pro-rata claims like creditors in bankruptcy, or would some jurisdictions give them senior claims like depositors?

Similarly, if a systemic stablecoin faced a run but remained solvent, would central banks provide liquidity support as they do for banks? Would emergency powers allow regulators to freeze redemptions temporarily? The lack of clarity creates uncertainty that could amplify panic during stress events.

The Tokenized Treasury Question: Regulators face particular challenges with tokenized Treasury products. Are these securities requiring full registration and prospectus delivery? Are they sufficiently similar to traditional Treasury ownership to deserve exemptions? Can they be integrated into DeFi protocols, or must they remain in restricted, permissioned environments?

The SEC has not provided comprehensive guidance, leaving issuers of tokenized Treasuries to structure products conservatively (limiting to accredited investors, relying on Regulation D exemptions, imposing transfer restrictions) to reduce regulatory risk. This constrains innovation and prevents tokenized Treasuries from achieving the composability and openness that would maximize their utility in DeFi.

Supervisory Capacity Challenges: Even where regulatory frameworks exist on paper, supervisory agencies often lack the resources, expertise, and technological capabilities to oversee crypto-native businesses effectively. Examining a traditional bank requires understanding credit underwriting, interest rate risk management, and loan portfolios. Examining a stablecoin issuer requires understanding blockchain technologies, cryptographic security, distributed ledger accounting, smart contract risks, and the unique operational characteristics of 24/7 global digital assets.

Regulatory agencies are hiring staff with crypto expertise and building internal capabilities, but this takes time. The gap between regulatory ambition and supervisory capacity creates risks that compliance failures may go undetected until problems become severe.

The overall regulatory picture is one of gradual convergence toward stricter oversight, but with significant gaps, inconsistencies, and unknowns. The direction is clear: major jurisdictions are moving toward treating systemic stablecoins more like regulated financial institutions. The timing, specific requirements, and enforcement approaches remain uncertain, creating ongoing compliance challenges for issuers and risk for users.

Case Studies & Evidence

Examining specific stablecoin issuers and their reserve strategies provides concrete illustrations of the dynamics discussed throughout this analysis. These case studies demonstrate both the diversity of approaches and the common gravitational pull toward Treasury exposure.

Circle and USDC: The Transparency Leader

Circle Internet Financial launched USD Coin in 2018 as a joint venture with Coinbase under the Centre Consortium governance framework. From the beginning, Circle positioned USDC as the transparent, compliant alternative to Tether, emphasizing regulatory cooperation and comprehensive attestations.

USDC's reserve evolution illustrates the broader industry trajectory. Initially, reserves consisted primarily of cash held at multiple FDIC-insured banks. By early 2021, Circle had begun holding a portion of reserves in short-duration U.S. Treasury securities and Yankee certificates of deposit. The company maintained that this mix provided both yield and liquidity while preserving safety.

However, Circle faced criticism for lack of transparency about exact composition percentages and the credit quality of its commercial paper holdings. Following pressure from regulators and the crypto community, Circle announced in August 2021 that it would transition USDC reserves entirely to cash and short-duration U.S. Treasuries, eliminating commercial paper and other corporate debt.

By September 2023, Circle had fully executed this transition. Monthly attestations showed that nearly 100% of reserves consisted of the Circle Reserve Fund (managed by BlackRock and investing exclusively in Treasuries and Treasury repo) plus cash at regulated banks. The October 2023 attestation reported approximately $24.6 billion in total reserves supporting $24.6 billion in outstanding USDC, with roughly $23.8 billion in the Reserve Fund and $800 million in cash (Circle Reserve Report, October 2023).

This composition remained stable through 2024. Circle's July 2024 attestation showed total reserves of approximately $28.6 billion, with $28.1 billion in the BlackRock-managed Reserve Fund invested in Treasuries and repo, and $500 million in cash at banking partners including Bank of New York Mellon and Citizens Trust Bank (Circle Reserve Report, July 2024).

The implications are striking: Circle's entire business model now depends on capturing yield from Treasury investments while paying nothing to USDC holders. In a 5% rate environment, that $28 billion generates approximately $1.4 billion in annual gross interest income. After operational expenses (likely in the $200-400 million range given Circle's technology, compliance, and banking costs), Circle's USDC operations could produce around $1 billion in annual net income, generated purely from the spread between its cost of capital (zero) and Treasury yields.

Circle's transparency, while industry-leading, still leaves questions. The monthly attestations are point-in-time snapshots, not continuous audits. They do not disclose the specific maturity distribution of Treasury holdings within the Reserve Fund, counterparty exposures in repo transactions, or detailed liquidity modeling. Nevertheless, Circle's approach represents the strongest disclosure regime among major stablecoin issuers and has become the de facto standard that regulators reference.

Tether and USDT: The Controversial Giant

Tether Limited launched USDT in 2014 as the first major stablecoin, initially marketed as fully backed by U.S. dollars in bank accounts. For years, Tether faced persistent questions about its reserve adequacy, transparency, and corporate governance. Critics alleged that Tether lacked full backing, commingled reserves with affiliated entities including Bitfinex exchange, and misrepresented its reserve composition.

These concerns culminated in a February 2021 settlement with the New York Attorney General's office. Tether agreed to pay $18.5 million in penalties and cease trading activity with New York residents, and most significantly, committed to enhanced transparency through quarterly public reporting on reserve composition.

Tether's subsequent reserve disclosures revealed substantial evolution. The Q2 2021 attestation showed that only approximately 10% of reserves consisted of cash and bank deposits, while roughly 65% were in commercial paper and certificates of deposit, 12% in corporate bonds and precious metals, and other assets making up the remainder (Tether Transparency Report, Q2 2021). This composition triggered significant concern; Tether held tens of billions in commercial paper from unknown counterparties, potentially including Chinese property developers and other risky credits.

Following pressure from regulators and market participants, Tether began transitioning toward safer assets. By Q4 2022, Tether reported that over 58% of reserves consisted of U.S. Treasury bills, with another 24% in money market funds (which themselves invest primarily in Treasuries and repo), approximately 10% in cash and bank deposits, and smaller allocations to other assets (Tether Transparency Report, Q4 2022).

This trend continued through 2023-2024. The Q2 2024 attestation showed Tether's reserve composition had shifted even further toward government securities: approximately 84.5% of roughly $118 billion in reserves consisted of cash, cash equivalents, overnight reverse repo, and short-term U.S. Treasury bills (Tether Transparency Report, Q2 2024). Tether disclosed holding over $97 billion in U.S. Treasury bills, making it one of the largest Treasury bill holders globally.