While Western headlines fixate on cryptocurrency speculation, a fundamentally different digital currency revolution is happening in the Global South. Across Nigeria, Kenya, Venezuela, and the Philippines, 1.4 billion unbanked adults are using Bitcoin, Ethereum, and stablecoins as essential survival tools rather than investments. They're sending remittances at a fraction of traditional costs, protecting savings from hyperinflation, and accessing cross-border payments that banks simply refuse to provide.

Ray Youssef still remembers the calls that came in the middle of the night. Desperate users from Nigeria, Kenya, Venezuela reaching across time zones because a remittance payment hadn't cleared, because a business deal hung in the balance, because families were waiting for money that traditional banking systems had frozen or delayed for days.

As the founder of Paxful and now CEO of NoOnes, Youssef fielded these emergency calls at three in the morning from unbanked users who had nowhere else to turn.

"I remember taking calls at three in the morning from unbanked users who were desperate to move money or make payments," Youssef recalls. "That's when I realised crypto's true potential."

While financial media in New York and London obsessed over Bitcoin's latest price swing or the newest meme coin sensation, these midnight calls represented a parallel cryptocurrency economy operating far from the trading charts. For billions of people in the Global South, digital currencies aren't speculative investments or get-rich-quick schemes.

They're essential infrastructure for survival, a lifeline connecting people to the global economy in places where traditional banking has systematically failed.

In this article we explore the growing gap between Western cryptocurrency discourse centered on speculation and institutional adoption, and the on-the-ground reality in emerging markets where digital currencies function as critical financial tools. Drawing on data from the World Bank, Chainalysis, central banks, and interviews with operators like Youssef who work directly with underserved populations, we explore how cryptocurrency is addressing financial exclusion in regions home to 1.4 billion unbanked adults.

The story of cryptocurrency in the Global South challenges prevailing narratives about digital assets. It's a story not of volatility and speculation, but of small business owners in Lagos, farmers in Ghana, students in the Philippines, and mothers in Venezuela using digital currencies to solve immediate, practical problems that traditional finance hasn't addressed in decades.

Understanding this reality requires looking past the headlines and examining the structural reasons why, in many parts of the world, cryptocurrency has become indispensable.

The Banking Gap – Why Traditional Finance Fails Emerging Markets

The Scope of Financial Exclusion

The numbers tell a stark story about who gets access to the global financial system and who remains on the outside. According to the World Bank's 2025 Global Findex Database, approximately 1.4 billion adults worldwide still lack access to a financial account at a bank or mobile money provider.

While global account ownership has increased dramatically over the past decade - from 51 percent in 2011 to 79 percent in 2025 - the remaining unbanked population faces formidable barriers to financial participation.

The geographic distribution of financial exclusion reveals deep inequalities. In developing economies, account ownership reached 71 percent by 2021, a 30 percentage point increase since 2011. Yet this aggregate figure masks substantial regional variations. Sub-Saharan Africa lags significantly, with only 40 percent of adults in the region holding accounts as of 2021. In some countries within the region, the majority of adults remain entirely outside the formal financial system.

Gender disparities compound these geographic inequalities. Women comprise 55 percent of the global unbanked population. The World Bank estimates that approximately 742 million women in developing countries lack access to formal financial services. In developing economies, the gender gap in account ownership has narrowed from nine percentage points in 2017 to six percentage points in 2021, representing progress but also highlighting how far the financial system must go to achieve gender parity.

Women's World Banking notes that unbanked women are 25 percent less likely than men to say they could use a financial account self-sufficiently, pointing to deeper issues beyond mere account access.

The barriers to traditional banking access are multifaceted and interconnected. Distance to the nearest bank branch remains a significant obstacle, particularly in rural areas where banks see little profit incentive to establish physical infrastructure.

Minimum balance requirements and account maintenance fees price out precisely the populations most in need of safe places to store money. Documentation requirements, including government-issued identification, proof of address, and employment verification, exclude those working in informal economies or lacking stable housing.

For Ray Youssef's users, these barriers aren't abstract statistics. They're the farmer in Ghana who needs to purchase seed but has no bank account to receive payment for his harvest. They're the domestic worker in the Philippines sending money home to her family but facing remittance costs that devour a significant portion of her earnings. They're the small business owner in Nigeria unable to access international suppliers because local banks can't or won't facilitate cross-border transactions efficiently.

"I couldn't build solutions for a farmer in Ghana who needed to buy seed if my business was being suffocated by regulators thousands of miles away," Youssef explains, describing the tension between serving

the unbanked and navigating regulatory frameworks designed primarily for traditional financial institutions.

Infrastructure Failures and the Cost of Money Movement

The problems with traditional banking in emerging markets extend beyond simple account access. Even those with accounts frequently encounter infrastructure so inadequate that it fails to meet basic financial needs. Cross-border money transfers exemplify these failures most clearly.

Remittances represent a crucial lifeline for hundreds of millions of people globally. In 2024, remittances to low and middle-income countries reached an estimated $905 billion, according to World Bank data.

These flows have grown to exceed both Foreign Direct Investment and Official Development Assistance to these regions. For many families, remittances from relatives working abroad provide essential income for food, education, healthcare, and housing.

Yet the cost of sending these remittances remains stubbornly high. The World Bank's Remittance Prices Worldwide database, which tracks costs across 367 country corridors, shows that the global average cost of sending $200 in remittances stood at 6.49 percent in the first quarter of 2025. This figure is more than double the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal target of three percent, established under SDG 10.c.

Regional disparities make these averages even more troubling. Sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the highest proportion of unbanked adults, also faces the highest remittance costs. As of the second quarter of 2024, sending $200 to Sub-Saharan Africa cost an average of 8.37 percent. Some corridors see costs exceeding 10 percent, meaning that someone sending money home loses more than $20 for every $200 transferred.

The choice of service provider dramatically affects these costs. Banks remain the most expensive channel for remittances, charging an average of 13.40 percent in the second quarter of 2024.

Traditional money transfer operators like Western Union and MoneyGram charge lower fees but still averaged 6.56 percent during the same period. Digital-only money transfer services offer somewhat better rates at 4.24 percent, but access to these services requires internet connectivity, smartphone access, and often bank accounts in both sending and receiving countries.

These percentage costs translate into billions of dollars annually extracted from the world's poorest populations. If remittance costs globally were reduced to the three percent target, families dependent on remittances would save an additional $20 billion per year, according to United Nations estimates. That's $20 billion that could instead go toward food, education, healthcare, and small business investment.

Beyond cost, speed presents another challenge. Traditional remittance transfers can take anywhere from several hours to several days to complete, depending on the corridor and service provider. During this time, families may wait anxiously for money needed for immediate expenses.

Banks often hold funds for compliance reviews, and correspondent banking relationships - where banks maintain accounts with each other to facilitate international transfers - have been declining, particularly for smaller and emerging market banks perceived as higher risk.

Youssef observed these failures firsthand through Paxful's operations. "Families are sending money across borders where banks refuse to cooperate. Women are no longer standing in line for hours at money transfer offices that charge outrageous fees," he notes, describing how users turned to cryptocurrency to solve problems that traditional finance hadn't addressed despite decades of supposed efforts toward financial inclusion.

Currency Instability and Capital Controls

In many emerging markets, the problems with traditional finance extend beyond infrastructure inadequacy to fundamental instability in the currencies themselves. Inflation, currency depreciation, and capital controls create environments where holding local currency becomes an act of financial self-sabotage.

Nigeria offers a vivid case study. The naira has experienced dramatic depreciation in recent years, plummeting to record lows in February 2024. High inflation rates - exceeding 20 percent at the beginning of 2023 and reaching even higher levels subsequently - erode the purchasing power of savings.

The government's 2022 decision to redesign the naira and introduce new notes, ostensibly to combat inflation and counterfeiting, instead triggered a cash shortage that placed enormous pressure on the country's substantial unbanked population.

Venezuela presents an even more extreme example. Hyperinflation rendered the bolivar essentially worthless, with the inflation rate reaching incomprehensible levels. Citizens saw their life savings evaporate and struggled to buy basic necessities as prices changed daily or even hourly. Access to U.S. dollars through official channels remained highly restricted, forcing people into black markets with worse exchange rates and legal risks.

Argentina, Turkey, Ghana, and Zimbabwe have all experienced their own versions of currency crises in recent years. In Ghana, inflation reached 29.8 percent in June 2022 after 13 consecutive months of increases, marking its highest level in two decades. Each crisis follows similar patterns: government fiscal mismanagement, declining foreign exchange reserves, restrictions on access to stable foreign currencies, and populations scrambling to preserve what little wealth they have.

Capital controls exacerbate these problems. Many governments, desperate to prevent capital flight and stabilize local currencies, impose restrictions on how much foreign currency citizens can purchase or hold.

These controls often fail to achieve their stated aims while successfully trapping ordinary citizens in depreciating local currencies. The wealthy and politically connected typically find ways around such restrictions, leaving the middle class and poor to bear the brunt of economic mismanagement.

Traditional banks in these environments become not safe havens for savings but rather custodians of steadily depreciating assets. Even when banks offer interest on deposits, the rates rarely keep pace with inflation. The purchasing power of money saved in a bank account gradually diminishes, punishing the responsible behavior of saving rather than immediately spending.

The Trust Deficit

Underlying all these structural problems lies a fundamental crisis of trust. Banking failures, government seizures of assets, corruption, and the general unreliability of institutions have taught populations in many emerging markets that placing faith in official financial systems is a recipe for disappointment or disaster.

Historical banking crises dot the landscape of many developing countries. Bank runs, insolvencies, and failures to honor deposit insurance schemes have wiped out savings and left populations wary of entrusting money to financial institutions. In some cases, governments have seized private bank accounts to address fiscal emergencies. In others, currency redenominations have effectively confiscated wealth.

Corruption within banking systems further undermines trust. Employees demand bribes to process transactions or open accounts. Well-connected individuals receive preferential treatment while ordinary citizens face bureaucratic obstacles.

Loan decisions depend more on personal relationships than creditworthiness. When the system operates on patronage rather than rules, those without connections find themselves perpetually disadvantaged.

This trust deficit creates a vicious cycle. Lacking faith in banks, people keep their savings in cash or physical assets like gold, making them vulnerable to theft, loss, and inflation. Without formal financial records, they struggle to build credit histories or access loans. Unable to participate fully in the formal economy, they remain trapped in informal systems with higher costs and less protection.

Youssef identifies this trust deficit as central to cryptocurrency's appeal in emerging markets. "Ethereum's smart contracts enable trust in environments where institutions have notoriously failed," he explains.

When traditional institutions have proven untrustworthy, the transparent, rules-based nature of blockchain technology offers an alternative. Smart contracts execute automatically according to their code, without requiring trust in intermediaries who might be corrupt, incompetent, or simply absent.

The Regulatory Divide – When Compliance Conflicts with Access

The U.S. Regulatory Framework and Operation Chokepoint 2.0

Understanding cryptocurrency's role in emerging markets requires examining why serving these populations from traditional financial centers like the United States has become nearly impossible. Ray Youssef's journey from building Paxful in the U.S. to relocating his operations for NoOnes illustrates the regulatory pressures that can make financial inclusion a casualty of compliance regimes.

"The US regulatory environment made it almost impossible to serve the people who needed crypto the most, especially in the Global South," Youssef states bluntly. "Accounts were being frozen, transactions flagged, and the basic utility was being stripped away."

The evolution of cryptocurrency regulation in the United States has been marked by increasing scrutiny and what many in the industry describe as regulatory hostility. Following the initial boom in cryptocurrency adoption and the 2017 bubble, regulators began applying existing financial regulations more stringently to digital asset businesses.

The Bank Secrecy Act's anti-money laundering provisions, know-your-customer requirements, and suspicious activity reporting obligations were extended to cryptocurrency exchanges and service providers.

These compliance requirements aren't inherently problematic. Preventing money laundering, terrorist financing, and other illicit activities represents legitimate regulatory goals. However, the way these regulations have been applied to cryptocurrency businesses, particularly those serving global populations, has created what industry participants describe as a coordinated effort to cut crypto companies off from traditional banking services.

This alleged campaign, termed "Operation Chokepoint 2.0" in reference to an earlier Obama-era program that targeted other disfavored industries, came into sharp focus in early 2023. In January of that year, federal banking regulators - the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency - issued a joint statement warning banks about "Crypto-Asset Risks to Banking Organizations."

The statement outlined various risks including legal uncertainties, safety and soundness concerns, fraud, contagion, and stablecoin run risk.

Shortly thereafter, three crypto-friendly banks collapsed in rapid succession. Silvergate Bank entered voluntary liquidation in March 2023. Silicon Valley Bank failed and was taken over by regulators. Signature Bank was shut down by New York regulators.

While each bank had specific issues contributing to its demise, the timing and the government's subsequent actions led many to suspect a coordinated effort to drive cryptocurrency businesses out of the U.S. banking system.

Internal FDIC communications obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests by Coinbase appeared to confirm these suspicions. The heavily redacted documents revealed "pause letters" sent by the FDIC to banks under its supervision, actively discouraging them from banking cryptocurrency companies.

At least 25 such letters were sent to banks between 2022 and 2023. The letters reportedly demanded onerous compliance information while being unclear about what was actually required before the agency would approve the provision of financial services to crypto businesses.

More than 30 technology and cryptocurrency founders reported being "debanked" - having their bank accounts closed without clear explanation or recourse. Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen brought national attention to the issue during a November 2024 appearance on Joe Rogan's podcast, describing how his firm saw founders systematically cut off from banking services. Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong called the debanking effort "unethical and un-American."

The impact on cryptocurrency businesses serving global populations was severe. Companies faced a choice: curtail their services, particularly to higher-risk jurisdictions where their services were most needed, or risk losing access to U.S. banking entirely. Many chose the former. Some, like Youssef, chose to relocate operations outside the United States.

"That was the turning point for me," Youssef explains. "I couldn't build solutions for a farmer in Ghana who needed to buy seed if my business was being suffocated by regulators thousands of miles away."

The underlying tension reveals a fundamental conflict between financial inclusion and risk-based compliance frameworks. Serving unbanked populations in the Global South means accepting customers without traditional documentation, operating in jurisdictions with weaker anti-money laundering controls, and processing transactions that pattern-matching algorithms flag as potentially suspicious.

From a regulator's risk perspective, these factors make such customers and businesses undesirable. From a financial inclusion perspective, they represent precisely the populations most in need of services.

Global South Regulatory Approaches

While the United States and other developed economies have moved toward increasingly restrictive approaches to cryptocurrency, some emerging markets have experimented with more innovative regulatory frameworks. Their governments, facing different challenges and recognizing cryptocurrency's potential to address financial inclusion gaps, have sometimes proven more willing to embrace digital currencies.

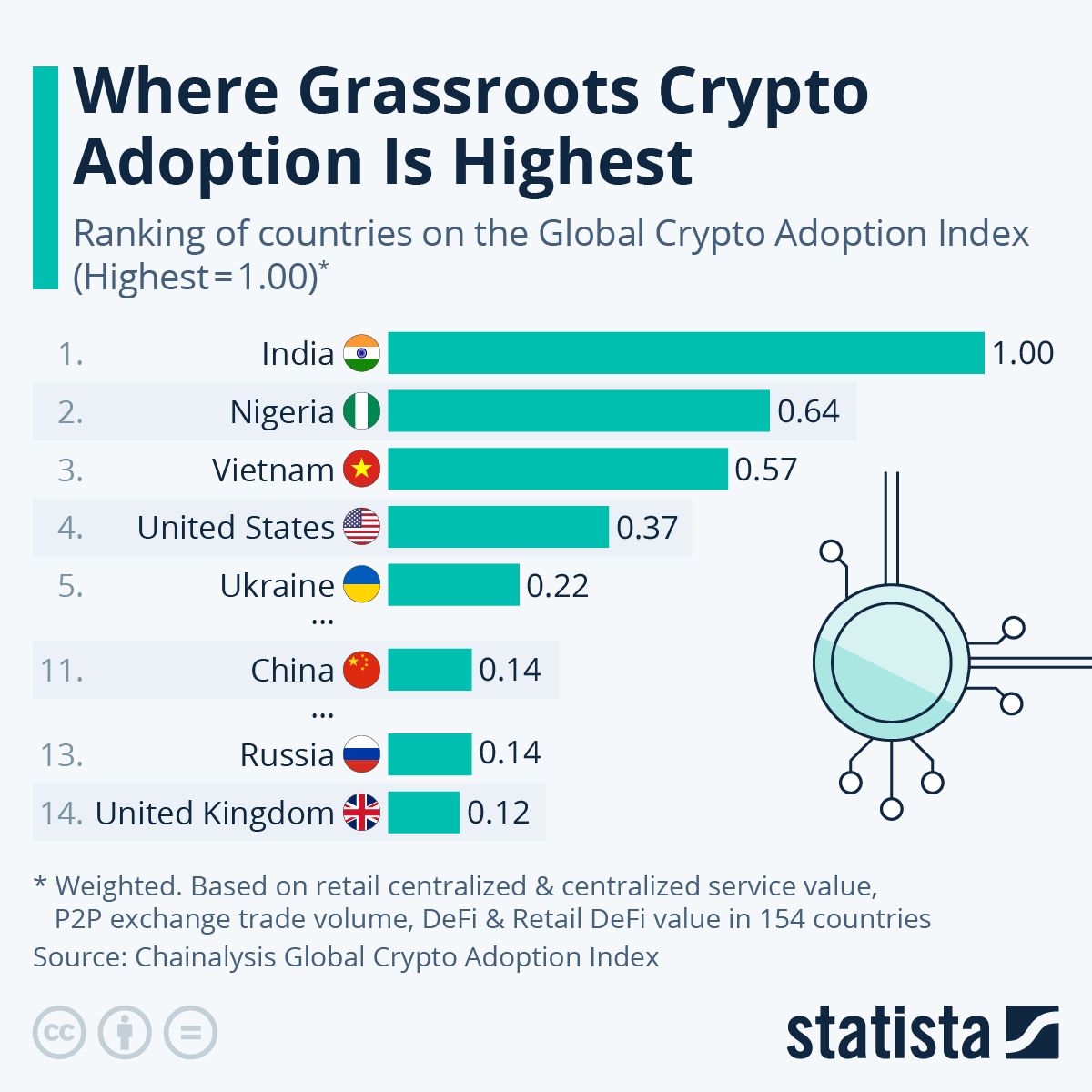

Nigeria presents a complex and evolving regulatory picture. Despite ranking second globally on Chainalysis's 2024 and 2025 Global Crypto Adoption Indexes, Nigeria's government has had an ambivalent relationship with cryptocurrency.

In 2021, the Central Bank of Nigeria directed banks and financial institutions to close accounts of persons or entities transacting in or operating cryptocurrency exchanges. The directive effectively pushed cryptocurrency trading to peer-to-peer platforms operating outside traditional banking channels.

Simultaneously, the Nigerian government launched the eNaira, a central bank digital currency aimed at promoting financial inclusion and reducing transaction costs. Yet adoption of the eNaira has been minimal. International Monetary Fund data indicated that 98 percent of eNaira wallets were inactive by 2023. Nigerians clearly preferred dollar-backed stablecoins like USDT and USDC over the government's digital currency, suggesting that centralized government control wasn't the digital feature they sought.

More recently, Nigeria has shifted toward a regulatory sandbox model. The Securities and Exchange Commission began processing applications for cryptocurrency exchange and custodian licenses, though major exchanges like Binance have faced continued regulatory challenges.

In 2024, the SEC set up an eight-month regulatory sandbox for various cryptocurrency service providers and signaled support for real-world asset tokenization efforts. The regulatory environment remains in flux, operating in what observers describe as a gray zone where crypto isn't explicitly banned but also lacks clear legal support.

Despite - or perhaps because of - the regulatory uncertainty, cryptocurrency adoption in Nigeria has flourished. The country received approximately $92.1 billion in cryptocurrency value between July 2024 and June 2025, nearly triple that of the next African country, South Africa.

Around 85 percent of transfers were under $1 million in value, indicating primarily retail and professional-sized transactions rather than institutional activity. The regulatory restrictions failed to curb adoption and instead pushed users toward more decentralized solutions outside government control.

Kenya offers a different model. As a mobile money pioneer, Kenya built its approach to digital finance on the success of M-Pesa, the SMS-based mobile money platform launched by Safaricom. By 2021, 79 percent of Kenyan adults had some form of financial account, largely due to mobile money adoption. This existing digital financial infrastructure created a foundation for cryptocurrency integration.

Kenyan regulators have taken a more measured approach to cryptocurrency, neither banning it outright nor providing comprehensive regulatory clarity. The Capital Markets Authority has warned about risks while also acknowledging cryptocurrency's potential. Banks remain wary of directly servicing cryptocurrency exchanges, but peer-to-peer trading thrives. The government has begun exploring how cryptocurrency might complement rather than threaten its mobile money success.

El Salvador's Bitcoin experiment represents the most radical approach by any government. In September 2021, El Salvador became the first country to adopt Bitcoin as legal tender alongside the U.S. dollar. The government developed the Chivo wallet, provided citizens with $30 in Bitcoin to encourage adoption, and installed Bitcoin ATMs throughout the country.

While the initiative generated significant international attention and controversy, actual adoption by Salvadorans for everyday transactions has been mixed. Many continue using the U.S. dollar for most purchases, though remittance flows through Bitcoin rails have shown some promise.

South Africa has emerged as a regulatory leader in Sub-Saharan Africa. The country established comprehensive licensing requirements for virtual asset service providers, creating regulatory certainty that attracted more institutional participation.

With hundreds of registered cryptocurrency businesses already licensed, South Africa demonstrates how clear regulatory frameworks can foster both innovation and consumer protection. The result is visible in the data: South Africa shows substantially higher institutional activity than most other African markets, with large-ticket volumes driven by sophisticated trading strategies.

The Compliance-Access Paradox

These varied regulatory approaches highlight a fundamental tension in financial regulation: the more stringently regulators apply know-your-customer and anti-money laundering requirements, the more they exclude precisely the populations most in need of financial services.

Traditional KYC requirements demand government-issued identification, proof of address, and verification of employment or income. These requirements make perfect sense for populations with stable addresses, formal employment, and government documentation. They become insurmountable barriers for the billions working in informal economies, living in temporary housing, or residing in areas where government services barely function.

Proof of address requirements illustrate the problem. In many parts of the Global South, addresses don't follow standardized formats. Rural areas may lack street names or house numbers. Utility bills - a common form of address verification - may be in someone else's name or not exist at all for households without formal utility connections. Telling someone in such circumstances that they need proof of address to access financial services is effectively telling them they cannot access those services.

Employment verification presents similar challenges. The International Labour Organization estimates that approximately 61 percent of the global employed population works in the informal economy.

These workers - street vendors, domestic workers, agricultural laborers, small-scale traders - earn incomes and need financial services but cannot provide employer verification letters or paycheck stubs.

The risk-based approach that regulators favor compounds these problems. Under risk-based frameworks, financial institutions must assess the money laundering and terrorist financing risks of potential customers and apply enhanced due diligence to higher-risk categories.

Customers from countries with weaker financial regulations, those working in cash-intensive businesses, and those unable to provide standard documentation automatically fall into higher-risk categories. Enhanced due diligence then demands additional verification steps that these customers often cannot meet.

The result is a compliance framework that systematically excludes the poor, the informally employed, and those in regions with weak governance - precisely the populations facing the greatest financial exclusion. Banks and financial institutions, facing regulatory penalties for compliance failures, rationally choose to serve only customers who fit neatly into their risk matrices. The unbanked remain unbanked.

Youssef describes this regulatory reality as central to his decision to relocate operations. "It was always the mission for NoOnes in the Global South, with boots on the ground. Being close to the people I serve allows me to create financial products tailored to their needs, without the barriers that plagued us in the US."

Operating from jurisdictions with different regulatory priorities allows companies like NoOnes to maintain focus on financial inclusion rather than merely compliance theater. Alternative identity verification methods, such as social verification, reputation systems, and graduated access based on transaction history, become possible.

The emphasis shifts from preventing all possible risk to enabling financial access while managing risk appropriately.

"My vision hasn't changed from day one," Youssef emphasizes. "It's just evolved to be more grounded, more focused on accessibility and fairness. Utility means nothing if people can't actually use it."

Use Cases on the Ground – How Crypto Functions in Daily Life

The abstract discussions of financial inclusion and regulatory frameworks find concrete expression in how millions of people actually use cryptocurrency day-to-day. Examining these real-world use cases reveals that for populations in the Global South, digital currencies solve immediate practical problems rather than serving as speculative investments.

Remittances: Sending Money Home

Remittances represent perhaps the clearest use case where cryptocurrency offers measurable advantages over traditional systems. The numbers speak for themselves. Traditional remittance channels charge an average of 6.49 percent globally, with costs reaching 8.37 percent for transfers to Sub-Saharan Africa and 13.40 percent when sent through banks.

A domestic worker in Dubai sending $200 home to her family in the Philippines through traditional channels might pay between $13 and $27 in fees, money that could otherwise buy several days' worth of food.

Cryptocurrency offers an alternative. Stablecoins like USDT and USDC enable transfers at a fraction of traditional costs. Even accounting for the fees to convert fiat currency to cryptocurrency on one end and back to fiat on the other end, total costs frequently run below three percent and sometimes below one percent. The speed advantage is equally significant. Cryptocurrency transfers settle in minutes to hours rather than the days required for traditional bank transfers.

The Philippines exemplifies how cryptocurrency remittances have taken hold. The country consistently ranks among the world's largest remittance recipients, with millions of overseas Filipino workers sending money home. In 2023, the Philippines received substantial cryptocurrency inflows, with the country ranking eighth on Chainalysis's Global Crypto Adoption Index.

Local cryptocurrency exchanges and peer-to-peer platforms have proliferated, making it easier for recipients to convert digital currencies to Philippine pesos or even spend certain cryptocurrencies directly.

Nigeria, as the largest remittance recipient in Africa with $19.5 billion received in 2023, has seen even more dramatic cryptocurrency adoption for cross-border transfers. Stablecoins accounted for approximately 40 to 43 percent of Nigeria's cryptocurrency transactions in 2024, driven largely by remittances and savings. The naira's instability and capital controls restricting access to U.S. dollars made dollar-pegged stablecoins particularly attractive.

Nigerians receiving remittances could hold value in a stable currency without relying on banks that might impose withdrawal restrictions or unfavorable exchange rates.

Mexico, despite its proximity to the United States and relatively developed financial infrastructure, has also seen growing cryptocurrency adoption for remittances. Mexican migrants in the United States, facing high costs from traditional money transfer services, increasingly turn to cryptocurrency to send money home. Local exchanges and peer-to-peer platforms in Mexico have made it easy for recipients to convert cryptocurrency to pesos, completing the remittance corridor.

Youssef's observation captures the human impact: "Families are sending money across borders where banks refuse to cooperate. Women are no longer standing in line for hours at money transfer offices that charge outrageous fees." These aren't abstract efficiency gains. They're hours saved, fees avoided, and money that arrives when families need it rather than when banks decide to release it.

Business and Commerce: Building Livelihoods

Beyond personal remittances, cryptocurrency has become a tool for business and commerce throughout the Global South. Traders, merchants, and small business owners use digital currencies to overcome obstacles that traditional banking places in their paths.

Peer-to-peer cryptocurrency trading has evolved into a significant economic sector. Platforms like LocalBitcoins, Paxful, and numerous regional alternatives created marketplaces where individuals could buy and sell cryptocurrency directly, often using local payment methods that global exchanges didn't support.

While LocalBitcoins shut down in 2023, contributing to a decline in measured peer-to-peer exchange volumes, the activity has shifted to other platforms and methods rather than disappearing.

Nigeria leads the world in peer-to-peer trading activity. Chainalysis data shows that Nigeria's peer-to-peer market remains vibrant despite regulatory pressures that forced many exchanges to shut down or restrict operations.

Traders operate through Telegram groups, WhatsApp, and local platforms, matching buyers and sellers and earning spreads on their trades. For many young Nigerians facing unemployment rates exceeding 30 percent for youth, cryptocurrency trading has become a viable source of income.

"Traders here are building businesses and creating jobs," Youssef notes. These aren't Wall Street investment firms. They're entrepreneurs with smartphones and internet connections, often operating from home or small offices, facilitating cryptocurrency transactions for their local communities. They've built businesses around arbitrage opportunities, exploiting price differences between local and international markets. They provide liquidity and access points for customers who want to buy or sell cryptocurrency but lack access to international exchanges.

Small and medium-sized businesses have adopted cryptocurrency for other purposes as well. Import-export businesses use it to settle invoices when traditional banking channels are slow or prohibitively expensive.

Online businesses that sell to international customers accept cryptocurrency to avoid the high fees and chargebacks associated with international credit card processing. Freelancers providing services to clients abroad receive payment in cryptocurrency rather than waiting days or weeks for international wire transfers.

The farmer in Ghana that Youssef mentioned isn't a hypothetical example. Agricultural businesses throughout Africa face significant challenges accessing working capital and transacting with suppliers. Banks rarely serve agricultural sectors in rural areas, seeing them as too risky and unprofitable. When farmers need to purchase seeds, fertilizer, or equipment, cryptocurrency can provide a means to receive payment for crops and make those essential purchases, operating outside banking systems that have failed to serve agricultural communities.

Savings and Wealth Preservation: Fighting Inflation

In economies experiencing high inflation or currency depreciation, cryptocurrency - particularly stablecoins - has become a savings vehicle for populations desperate to preserve wealth. The logic is straightforward: if local currency is losing value daily, holding a dollar-denominated stablecoin becomes a rational choice even considering the risks inherent in cryptocurrency.

Venezuela offers the most extreme example. As hyperinflation destroyed the bolivar's value, Venezuelans turned to cryptocurrency to preserve what little wealth they could. Remittances from relatives abroad arrived as cryptocurrency because traditional banking channels had become unreliable.

Local businesses began accepting Bitcoin and stablecoins for payment because they maintained value in ways the bolivar could not. The government's own Petro cryptocurrency failed to gain traction, but private stablecoins became a de facto parallel currency.

Argentina has seen similar patterns, though less extreme. With chronic inflation and capital controls restricting access to dollars, Argentinians have embraced cryptocurrency as a savings mechanism. Stablecoins like USDT trade at premiums on local exchanges, reflecting strong demand for dollar-denominated assets. The government's repeated currency crises have taught Argentinians that holding pesos is financially destructive, driving them toward alternatives.

Turkey's lira depreciation has likewise spurred cryptocurrency adoption. As the lira lost value against the dollar, Turkish citizens sought ways to preserve purchasing power. Cryptocurrency exchanges saw surges in trading volume during periods of particular lira weakness. While the government has imposed some restrictions on cryptocurrency usage, the fundamental driver - currency instability - ensures continued demand.

Chainalysis data on Nigeria shows the practical manifestation of this dynamic. In Q1 2024, stablecoin value approached almost $3 billion, making stablecoins the largest portion of sub-$1 million transactions in Nigeria. This surge coincided with the naira hitting record lows, demonstrating the direct connection between currency instability and stablecoin adoption. Nigerians weren't speculating on stablecoin price appreciation - the whole point of stablecoins is that they don't appreciate. They were simply trying to prevent their savings from evaporating along with the naira's value.

"People are starting to see the real-world utility of cryptocurrency, especially in day-to-day transactions, which is a shift from the earlier view of crypto as just a get-rich-quick scheme," explains Moyo Sodipo, COO and Co-founder of Nigerian exchange Busha. "When Busha gained popularity around 2019 and 2020, there was a big frenzy for Bitcoin. A lot of people were not initially keen on stablecoins. Now that Bitcoin has lost a lot of its value [from peaks], there is a desire for diversification between Bitcoin and stablecoins."

The shift from Bitcoin to stablecoins for savings purposes reflects maturation in how cryptocurrency is used. While Bitcoin's price volatility can work in investors' favor during bull markets, it presents unacceptable risk for those trying to preserve value rather than speculate.

Stablecoins provide the key attributes that make cryptocurrency useful for savings - independence from local financial systems, easy transferability, divisibility - without the volatility that makes Bitcoin unsuitable as a store of value for those who can't afford to lose any purchasing power.

Education and Social Mobility: Accessing Opportunities

International education presents another domain where cryptocurrency solves practical problems that traditional finance handles poorly. Students from emerging markets face significant hurdles when trying to pay tuition and living expenses abroad.

Bank transfers are expensive and slow. Credit cards may not work internationally or carry high foreign transaction fees. Some countries impose limits on how much foreign currency can be purchased for education, treating students as potential vectors for capital flight.

Cryptocurrency enables students to receive money from family, pay tuition, and handle living expenses without depending on banks that view them as inconvenient customers. Educational institutions in some countries have begun accepting cryptocurrency directly for tuition payments, recognizing both the demand from international students and the efficiency gains from eliminating banking intermediaries.

Scholarship and grant distribution through cryptocurrency has also emerged as a use case. Non-governmental organizations and foundations providing financial support to students or entrepreneurs in emerging markets can distribute funds as cryptocurrency, ensuring money reaches intended recipients quickly and with minimal leakage to intermediaries. Recipients can then convert to local currency as needed or, increasingly, use stablecoins directly for certain purchases.

The global freelance economy, enabled by platforms like Upwork, Fiverr, and numerous others, creates opportunities for skilled workers in emerging markets to earn income from clients worldwide. Yet payment friction has historically limited participation. International wire transfers cost $25 to $50 per transaction, making small payments economically impractical.

PayPal and similar services restrict or charge high fees in many countries. Cryptocurrency provides freelancers a means to receive payment efficiently, particularly for smaller amounts where traditional payment processing fees would be prohibitive.

A graphic designer in Pakistan completing a $200 project for a client in the United States faces a choice. A bank wire transfer might cost $40 and take a week. PayPal, if available, charges approximately five percent plus currency conversion fees. Cryptocurrency payment might cost $5 to $10 all-in and arrive within hours. The mathematics strongly favor cryptocurrency, allowing the freelancer to keep more of her earnings and the client to pay less in transaction costs.

Youssef notes this impact directly: "Students are using it to scrape together enough funds for their education. That's not speculation, instead, it's survival, it's empowerment." The distinction matters. Critics dismiss cryptocurrency as speculative and therefore unworthy of serious policy consideration.

But for students struggling to fund their education or freelancers trying to collect payment for their work, cryptocurrency's speculative aspects are irrelevant. What matters is whether it solves their immediate problem of moving money efficiently.

Humanitarian Aid and Crisis Response

Recent years have demonstrated cryptocurrency's potential in humanitarian contexts. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, cryptocurrency donations to Ukrainian organizations and the government surged. The speed and borderless nature of cryptocurrency enabled individuals and organizations worldwide to contribute directly to relief efforts.

Traditional donation channels through banks and international organizations involved substantial delays and administrative overhead. Cryptocurrency reached recipients within hours.

Non-governmental organizations operating in challenging environments have begun exploring cryptocurrency for aid distribution. Traditional methods of delivering financial assistance face numerous obstacles: banking infrastructure may be damaged or nonexistent, government interference may block or skim funds, beneficiaries may lack bank accounts or identification documents. Distributing assistance as cryptocurrency loaded onto simple mobile wallets can circumvent many of these problems.

The Syrian refugee crisis illustrated this potential. Refugees, having fled with little documentation and unable to open bank accounts in host countries, struggled to participate in formal economies. Some humanitarian organizations experimented with providing prepaid cards or mobile money, but these solutions had limitations.

Cryptocurrency offered another option: refugees could receive funds and make purchases through cryptocurrency-accepted by participating merchants, or convert to local currency through peer-to-peer platforms.

Natural disaster response provides another context. When hurricanes, earthquakes, or floods destroy infrastructure including banks and payment systems, cryptocurrency can continue functioning as long as mobile networks remain operational or are quickly restored. Disaster victims can receive aid directly to mobile wallets, maintaining financial access during recovery periods when traditional banking may be unavailable.

While humanitarian cryptocurrency usage remains relatively small compared to commercial applications, it demonstrates the technology's resilience and utility in circumstances where traditional financial infrastructure fails. These edge cases also provide valuable lessons about what makes cryptocurrency genuinely useful: not price speculation or investment returns, but the ability to move value efficiently in contexts where other options don't work well or don't work at all.

The Technology Layer – Why Ethereum and Smart Contracts Matter

Bitcoin pioneered cryptocurrency and remains the most recognized digital currency, but the evolution of blockchain technology beyond Bitcoin has expanded cryptocurrency's utility significantly. Ethereum and other smart contract platforms have enabled applications that extend far beyond simple value transfer.

Beyond Bitcoin: Programmable Money

Bitcoin's design focuses on doing one thing well: being a decentralized digital currency that no government or corporation controls. This focused design gives Bitcoin certain advantages, particularly as a store of value and censorship-resistant payment system. However, Bitcoin's scripting language is intentionally limited to prevent complex operations that might introduce security vulnerabilities.

Ethereum, launched in 2015, took a different approach. Rather than being solely a currency, Ethereum is a platform for running decentralized applications using smart contracts - code that executes automatically according to predefined rules without requiring intermediaries. This programmability transforms cryptocurrency from merely a payment rail into an infrastructure for building financial services.

Youssef recognizes this transformative potential: "Ethereum's smart contracts enable trust in environments where institutions have notoriously failed." When traditional institutions are corrupt, incompetent, or simply absent, smart contracts offer an alternative. If two parties want to enter a financial agreement, they can encode the terms in a smart contract that automatically executes when conditions are met. Neither party needs to trust the other or rely on a court system to enforce the agreement - the code enforces itself.

This might sound like a technical distinction without practical importance, but in environments where institutional trust is low, it fundamentally changes what's possible. A farmer can receive payment for crops automatically when delivery is confirmed, without worrying whether the buyer will actually pay.

A freelancer can ensure payment releases when work is completed satisfactorily, without depending on a platform operator to mediate disputes fairly. A savings group can pool funds under transparent rules that prevent any single member or operator from misappropriating money.

DeFi: Reconstructing Financial Services

Decentralized Finance, or DeFi, represents the application of smart contract technology to rebuild financial services without traditional intermediaries. Lending, borrowing, trading, insurance, and derivatives - all the functions banks and financial institutions provide - can be implemented as smart contracts running on blockchain networks.

The appeal of DeFi for emerging markets lies in eliminating gatekeepers who have historically excluded certain populations. Traditional banks decide who gets loans based on credit histories, collateral, and other factors that systematically disadvantage people in developing countries.

DeFi lending protocols don't care about your credit history or where you live. If you have cryptocurrency to post as collateral, you can borrow. If you want to earn interest on your savings, you can supply liquidity to lending pools without meeting minimum balance requirements or paying account fees.

Nigeria has emerged as a leader in DeFi adoption globally, receiving over $30 billion in value through DeFi services in 2023. Sub-Saharan Africa more broadly leads the world in grassroots DeFi usage as measured by the proportion of transactions that are retail-sized. This isn't wealthy investors in Lagos making massive trades. It's ordinary Nigerians using DeFi platforms to access financial services that traditional banks haven't provided.

The use cases vary. Some users participate in yield farming, providing liquidity to decentralized exchanges and earning trading fees. Others use lending protocols to borrow stablecoins against their cryptocurrency holdings, accessing dollar-denominated liquidity without selling their crypto or going through banks.

Still others use DeFi for more sophisticated purposes like hedging currency risk or accessing derivatives that would be unavailable through traditional financial institutions in their countries.

Youssef frames DeFi's importance in structural terms: "ETH offers a way to build decentralized services like lending, remittances, or savings platforms that operate outside of traditional gatekeepers... as part of the toolkit to dismantle what I call financial apartheid."

The phrase "financial apartheid" deliberately evokes the systematic exclusion that characterized South Africa's apartheid regime. Youssef argues that the global financial system operates as a form of apartheid, where geographic location, wealth level, and documentation determine who gets access to financial services and who remains perpetually excluded.

DeFi, by eliminating traditional gatekeepers and operating according to transparent code rather than human discretion, offers a path to dismantle these exclusionary systems.

The Scalability Challenge

Despite its promise, Ethereum and similar smart contract platforms face significant scalability limitations that constrain their utility for mass adoption in emerging markets. Ethereum's transaction throughput - the number of transactions it can process per second - remains relatively low, typically ranging from 15 to 30 transactions per second depending on transaction complexity. When network demand exceeds this capacity, users compete for transaction inclusion by offering higher fees, driving up costs.

During periods of high network congestion, Ethereum transaction fees have exceeded $50 or even $100 per transaction. Such fees make Ethereum unusable for the small-value transactions that dominate emerging market usage. A remittance payment of $200 becomes economically irrational if it costs $50 to send. A $20 purchase can't be made on-chain if the transaction fee alone costs $30.

Youssef acknowledges this challenge directly: "It's not perfect, there are high fees and scalability have been real challenges, but it continues to evolve." The recognition that Ethereum has limitations while remaining optimistic about its evolution reflects the pragmatic stance necessary for actually deploying cryptocurrency solutions rather than purely theorizing about them.

Multiple approaches to addressing Ethereum's scalability limitations are developing. Layer 2 solutions - including Arbitrum, Optimism, Polygon, and others - process transactions off of Ethereum's main chain and periodically settle batches of transactions to the main chain. This approach increases throughput and reduces costs while maintaining security guarantees from Ethereum's base layer.

Layer 2 adoption has grown substantially. Hundreds of billions of dollars in value now transact on Layer 2 networks monthly, with transaction costs typically measuring in cents rather than dollars. For emerging market users, these Layer 2 networks offer a more practical path to accessing Ethereum-based applications and services. A user in Kenya can interact with DeFi protocols on Polygon, paying transaction fees of a few cents, making the technology economically viable for everyday usage.

Alternative Layer 1 blockchains with different design tradeoffs have also gained traction in certain regions. Solana, with higher throughput and lower fees than Ethereum, has seen adoption for applications where transaction cost is paramount. Binance Smart Chain, despite centralization tradeoffs, attracted users through low costs and compatibility with Ethereum-based applications. These alternative networks represent different points on the tradeoff curve between decentralization, security, and scalability.

The technology continues evolving. Ethereum's transition from Proof of Work to Proof of Stake in 2022 reduced energy consumption by over 99 percent and laid groundwork for future scalability improvements. Further upgrades promise to increase transaction throughput on the base layer. The combination of base layer improvements and Layer 2 solutions aims to provide the scalability necessary for billions of users.

Stablecoins: The Bridge Between Crypto and Commerce

Among cryptocurrency innovations, stablecoins may prove most immediately impactful for emerging market financial inclusion. Stablecoins are cryptocurrencies designed to maintain stable value relative to an underlying asset, most commonly the U.S. dollar.

Rather than fluctuating wildly like Bitcoin or Ethereum, stablecoins aim to provide cryptocurrency's benefits - fast, borderless transfer; programmability; censorship resistance - while maintaining price stability that makes them suitable for everyday transactions and savings.

Two stablecoins dominate usage in emerging markets: Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC). USDT processed over $1 trillion per month in transaction volume between June 2024 and June 2025, consistently dwarfing other stablecoins. USDC ranks second but with substantially lower volume. Both claim to be backed by reserves of U.S. dollars and short-term Treasury securities, allowing them to maintain the peg to the dollar.

Chainalysis data reveals stablecoins' particular importance in certain regions. In Sub-Saharan Africa, stablecoins accounted for 43 percent of cryptocurrency transaction volume between July 2023 and June 2024. In Nigeria specifically, stablecoins represented approximately 40 percent of the country's crypto market. These figures indicate that stablecoins aren't a minor feature but rather a core use case driving adoption.

The appeal is straightforward. In countries with unstable currencies and capital controls, dollar-pegged stablecoins offer a way to hold dollars without accessing official banking channels that may restrict or prohibit dollar holdings.

A Nigerian wanting to save in dollars faces obstacles: banks limit how many dollars can be purchased; official exchange rates may be significantly worse than parallel market rates; dollar savings accounts require documentation and minimum balances many people can't meet. Holding USDT circumvents all these obstacles, providing dollar exposure through a cryptocurrency wallet rather than a bank account.

For remittances, stablecoins offer the speed and low cost of cryptocurrency without requiring recipients to immediately convert to local currency at uncertain exchange rates. A person in India receiving a remittance as USDC can hold it in that form, preserving value in dollars, and convert to rupees gradually as needed for expenses. This flexibility allows recipients to optimize timing of conversion and avoid locking in poor exchange rates.

Merchants in some locations have begun accepting stablecoins directly, recognizing customer demand and the payment rail's efficiency. A business importing goods from international suppliers can pay in USDT rather than navigating slow and expensive international wire transfers. Online businesses serving international customers can accept stablecoin payments without chargebacks or the high fees associated with international credit card processing.

Stablecoins' growth has attracted regulatory attention, with governments and central banks expressing concerns about stablecoins potentially undermining monetary sovereignty. The European Union's Markets in Crypto-Assets regulation established a licensing framework for stablecoin issuers.

The United States passed the GENIUS Act creating regulatory requirements for stablecoin issuers. These regulatory developments aim to bring stablecoins within formal oversight while preserving their utility.

Challenges and Criticisms – A Balanced Assessment

Any honest examination of cryptocurrency's role in emerging markets must address legitimate criticisms and challenges. Cryptocurrency isn't a panacea for financial exclusion, and numerous concerns deserve serious consideration.

Illicit Finance Risks

The most frequently cited criticism of cryptocurrency centers on its use for illicit purposes including money laundering, terrorist financing, sanctions evasion, and various scams and frauds. These concerns aren't fabricated - cryptocurrency has indeed been used for illegal activities. The question is whether illicit use represents the primary usage or a minority of transactions, and whether it exceeds illicit use of traditional financial systems.

Chainalysis publishes annual Crypto Crime Reports tracking illicit cryptocurrency transaction volumes. The 2024 report found that illicit transaction volume reached $24.2 billion in 2023, representing approximately 0.34 percent of all cryptocurrency transaction volume that year.

While $24.2 billion is a substantial absolute number, the percentage of total volume is relatively low. For comparison, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that two to five percent of global GDP is laundered through traditional financial systems annually - a substantially higher percentage than cryptocurrency's illicit usage rate.

The types of illicit activities involve both traditional crimes conducted using cryptocurrency and new cryptocurrency-specific crimes. Ransomware attackers demand payment in Bitcoin, exploiting its pseudonymous nature to complicate law enforcement efforts. Darknet markets facilitate illegal drug sales using cryptocurrency. Sanctioned entities attempt to move money through cryptocurrency to evade restrictions. These represent genuine concerns.

However, cryptocurrency's public ledger nature actually aids law enforcement in ways that cash transactions do not. Every transaction on blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum is recorded permanently and publicly.

While addresses aren't directly tied to real-world identities, blockchain analysis firms can trace flows through the network, identify patterns, and link addresses to exchanges where identification verification occurred. Law enforcement agencies have successfully used blockchain analysis to investigate and prosecute crimes ranging from the Silk Road marketplace to sanctions violations.

For emerging market users engaging in legitimate commerce, illicit finance concerns create friction through compliance requirements that financial institutions impose to manage risk. An entrepreneur in Nigeria conducting entirely legal business may find her account flagged because she transacts frequently in cryptocurrency, an activity that pattern-matching algorithms associate with higher risk.

The challenge is developing compliance approaches that effectively target genuine illicit activity while not creating insurmountable barriers for legitimate users in regions where cryptocurrency serves essential functions.

Consumer Protection Gaps

Cryptocurrency's decentralized nature, while offering benefits of censorship resistance and independence from institutional gatekeepers, creates challenges for consumer protection. When someone makes a mistake sending cryptocurrency - sending to a wrong address, falling for a scam, or losing access to their wallet - there's no customer service to call, no transaction to reverse, no insurance fund to make them whole.

Scams targeting cryptocurrency users are widespread and sophisticated. Phishing schemes trick users into revealing private keys or seed phrases. Ponzi schemes promise unrealistic returns to attract deposits that later disappear. Pump-and-dump schemes artificially inflate prices of low-liquidity tokens before insiders sell.

Romance scams cultivate online relationships before convincing victims to send cryptocurrency. These scams particularly target populations with less technical sophistication and those desperate for financial opportunities.

Technical literacy represents a significant barrier to safe cryptocurrency usage. Properly securing a cryptocurrency wallet requires understanding concepts like private keys, seed phrases, secure storage, and transaction verification. Failing to understand these concepts leads to losses. Users might store private keys insecurely, making them vulnerable to theft. They might fall for fake wallets that steal funds. They might lose seed phrases and permanently lose access to their money.

The irreversibility of cryptocurrency transactions - a feature from a technical perspective - becomes a bug from a consumer protection perspective. If someone fraudulently convinces you to send them cryptocurrency, you can't call your bank to reverse the transaction. If you accidentally send cryptocurrency to the wrong address, it's gone.

Traditional financial systems build in reversibility and dispute resolution mechanisms precisely to protect consumers from mistakes and fraud. Cryptocurrency's design prioritizes different values.

Some solutions are emerging. Multisignature wallets require multiple parties to approve transactions, reducing risk of unilateral theft or mistakes. Smart contract-based escrow services provide some transaction reversibility under certain conditions. Insurance products covering certain types of cryptocurrency losses are developing. Exchange-based wallets provide familiar user experiences with customer support, though at the cost of users not controlling their private keys.

The fundamental challenge remains: providing sufficient consumer protection to make cryptocurrency safe for mainstream adoption while preserving the decentralization and censorship resistance that make it useful in contexts where institutions fail. This balance is difficult to achieve, and many emerging market users are currently left navigating these risks with insufficient protection.

Volatility Risks

While stablecoins address volatility concerns, many emerging market users hold Bitcoin, Ethereum, and other cryptocurrencies whose prices fluctuate dramatically. A person who converts their savings to Bitcoin at a market peak might see 50 percent or more of their value disappear during a downturn. For populations living close to subsistence, such losses can be devastating.

The volatility issue is particularly acute when cryptocurrency serves as a medium of exchange rather than merely an investment. A merchant accepting Bitcoin for payment faces uncertainty about the value they're receiving.

If Bitcoin drops 10 percent before they can convert to local currency, they've effectively given a 10 percent discount. Conversely, if Bitcoin rises 10 percent, the customer effectively overpaid. This volatility makes Bitcoin impractical for ordinary commerce, pushing users toward stablecoins for transactional purposes.

For those using cryptocurrency for savings or remittances, volatility creates difficult tradeoffs. Holding Bitcoin offers potential appreciation but risks depreciation. Holding stablecoins preserves value in dollar terms but offers no appreciation and may lose value relative to dollar inflation. Holding local currency in high-inflation environments guarantees value loss. No perfect option exists.

Market manipulation concerns compound volatility risks. Cryptocurrency markets, particularly for smaller tokens, are vulnerable to manipulation by large holders or coordinated groups. Pump-and-dump schemes that would be illegal and prosecutable in traditional securities markets often operate with impunity in cryptocurrency markets. Retail investors in emerging markets, often with limited financial literacy, become targets for these schemes.

Education and realistic expectations represent partial solutions. Users need to understand that Bitcoin isn't a stable store of value and that they should only hold amounts they can afford to lose. Stablecoins should be used for purposes requiring price stability. Diversification across multiple cryptocurrencies and assets can reduce risk. However, even well-informed users in emerging markets may feel they have no better options, leading them to accept volatility risks as preferable to the certain losses they'd face through currency depreciation or inability to access traditional financial services.

Infrastructure Limitations

Cryptocurrency's promise of financial inclusion assumes that target populations have the technological infrastructure to access and use it. This assumption doesn't hold uniformly across emerging markets. Internet connectivity, smartphone ownership, technical literacy, and reliable electricity all represent prerequisites that millions lack.

According to GSMA data, the smartphone gender gap has widened globally, reaching 18 percent in 2021 up from 15 percent previously. This translates to 315 million fewer women than men owning smartphones. Similarly, the mobile internet gender gap has stalled at 16 percent, representing 264 million fewer women using mobile internet.

For cryptocurrency to deliver on financial inclusion promises for women specifically, addressing these underlying connectivity gaps is essential.

Rural areas often lack reliable internet connectivity, making cryptocurrency transactions difficult or impossible. When connectivity exists, it may be prohibitively expensive for populations earning a few dollars daily.

A person who must choose between purchasing mobile data and buying food will prioritize food, leaving them unable to access cryptocurrency-based financial services that theoretically offer them opportunities.

Electricity availability, often taken for granted in developed economies, remains inconsistent in many parts of the Global South. When power outages occur frequently, keeping smartphones charged becomes a challenge. During extended outages, accessing cryptocurrency services becomes impossible regardless of internet availability.

Technical literacy barriers compound infrastructure limitations. Understanding how to set up and secure a cryptocurrency wallet, conduct transactions, verify addresses, and protect private keys requires education and practice. For populations with limited formal education and little prior experience with digital financial tools, the learning curve is steep. Well-designed user interfaces help, but significant gaps remain between cryptocurrency's current usability and the level required for truly broad adoption.

Environmental Considerations

Bitcoin's energy consumption has generated substantial criticism. Bitcoin's Proof of Work consensus mechanism requires miners to perform computationally intensive work to add blocks to the blockchain, consuming substantial electricity in the process.

Estimates of Bitcoin's annual energy consumption vary but generally fall in the range of 150 to 200 terawatt-hours, comparable to the energy consumption of a medium-sized country.

Critics argue that this energy consumption is wasteful and contributes to climate change, particularly when electricity is generated from fossil fuels. For emerging markets already facing energy access challenges, dedicating scarce energy resources to cryptocurrency mining seems particularly problematic. The environmental justice argument holds that wealthy investors' speculation shouldn't impose environmental costs on populations least able to bear them.

Defenders of Bitcoin's energy use argue that much of the energy comes from renewable sources or would otherwise be wasted, that energy consumption alone doesn't determine environmental impact without considering energy sources, and that traditional financial systems also consume substantial energy when accounting for bank branches, data centers, and other infrastructure.

They further contend that financial inclusion for billions justifies energy consumption, particularly as renewable energy becomes more available.

Ethereum's transition from Proof of Work to Proof of Stake in September 2022 dramatically reduced its energy consumption - by more than 99 percent according to the Ethereum Foundation. This transition demonstrates that blockchain technology doesn't inherently require massive energy consumption, and that environmental concerns can be addressed through technological evolution.

For cryptocurrency's role in emerging markets specifically, environmental concerns are important but represent one factor among many that must be balanced. A Nigerian using cryptocurrency to preserve savings against naira depreciation or a Kenyan receiving remittances through cryptocurrency rails isn't making that choice based on environmental impact. They're making it based on which option better meets their immediate financial needs. Long-term sustainability requires addressing environmental concerns through technological improvements rather than simply dismissing cryptocurrency usage in emerging markets.

The Decentralization Thesis – Resilience Through Distribution

Understanding why cryptocurrency continues growing in emerging markets despite obstacles requires grasping the significance of decentralization - not as an abstract technical feature but as a structural attribute that makes cryptocurrency resistant to suppression.

The Mosquitoes Metaphor

Youssef captures this concept vividly: "Crypto has already proven that it can't be stopped. First, governments tried to ban it, and when that failed, they tried to control it. But you can't kill an army of mosquitoes."

The mosquitoes metaphor, while crude, effectively communicates why centralized financial systems and decentralized cryptocurrency networks respond differently to government action. Shutting down a bank requires closing its branches, seizing its servers, and arresting its executives. Shutting down a centralized cryptocurrency exchange follows similar logic - identify the company, serve legal papers, freeze accounts, and the operation stops.

But shutting down Bitcoin or Ethereum the networks? Where do you serve the papers? Which servers do you seize? Bitcoin operates across tens of thousands of nodes run by individuals and organizations worldwide.

Ethereum has a similar distributed architecture. No single point of control exists. No headquarters to raid. No CEO to arrest. Governments can prohibit activities relating to these networks within their jurisdictions, but they cannot shut down the networks themselves.

This structural attribute explains cryptocurrency's persistence despite government opposition. When China banned cryptocurrency mining and trading, the ban successfully pushed these activities out of China.

Mining operations relocated to Kazakhstan, the United States, and elsewhere. Trading moved to offshore exchanges and peer-to-peer platforms. But Bitcoin and Ethereum continued operating, their networks unaffected by Chinese government action despite China having been the center of mining activity and a major market for trading.

Nigeria's experience illustrates the pattern. When the Central Bank of Nigeria directed banks to close cryptocurrency-related accounts in 2021, trading didn't stop. It shifted from centralized exchanges that connected to banks to peer-to-peer platforms that operated through more decentralized means.

Transaction volumes in Nigeria grew rather than declined following the ban, demonstrating the policy's ineffectiveness at achieving its stated goal of reducing cryptocurrency usage.

Network Effects and Adoption Curves

Cryptocurrency networks benefit from powerful network effects that drive adoption once critical mass is achieved. The value of a payment network increases exponentially as more participants join. A payment system with one million users offers limited utility. A payment system with one billion users becomes essential infrastructure. Each new user makes the network more valuable for all existing users, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of growth.

Bitcoin has achieved sufficient scale that shutting it down globally would require coordinated action by virtually all world governments, and even then, the network could survive in reduced form. Ethereum has reached similar scale. Smaller cryptocurrency networks remain more vulnerable to government action or market rejection, but the largest networks have established resilience through scale.

The adoption curve for cryptocurrency in emerging markets appears to follow the pattern of other transformative technologies. Early adopters, often more technically sophisticated and risk-tolerant, explore the technology and develop use cases.

As infrastructure improves and user experiences become more accessible, adoption broadens to mainstream users. Eventually, network effects and installed base make the technology difficult to displace even when alternatives emerge.

Several emerging markets have passed inflection points where cryptocurrency adoption has become self-sustaining. Nigeria, India, Vietnam, and others show transaction volumes and user bases that continue growing despite regulatory obstacles.

Local ecosystems have developed with exchanges, peer-to-peer traders, merchants accepting cryptocurrency, and services built around digital currencies. These ecosystems create constituencies with incentives to maintain and expand cryptocurrency usage.

Comparative Analysis: Other Censorship-Resistant Technologies

Cryptocurrency isn't the first technology to face government attempts at suppression, and examining how other censorship-resistant technologies have fared provides useful context. The internet itself, despite various governments' attempts to censor or control it, has proven largely resistant to shutdowns outside of specific authoritarian contexts.

File-sharing technologies offer particularly relevant comparisons. Napster, the first mainstream file-sharing service, operated as a centralized service and was successfully shut down through legal action. But the technology concept survived through increasingly decentralized implementations.

BitTorrent distributes files peer-to-peer without any central service to target. Despite decades of efforts by governments and copyright holders, BitTorrent continues operating because there's no central point of failure.

Encrypted messaging applications have followed similar patterns. When governments ban specific apps, users migrate to alternatives. Telegram, Signal, WhatsApp with end-to-end encryption, and others provide communications channels that governments can block but struggle to suppress entirely. The underlying technology - strong encryption - remains available to determined users regardless of government preferences.

Cryptocurrency's architecture borrows heavily from these previous generations of censorship-resistant technologies while adding financial functionality. The combination of peer-to-peer networking, cryptographic security, and economic incentives creates a system with robust resistance to suppression attempts.

Game Theory of Decentralized Systems

The persistence of decentralized systems despite government opposition reflects underlying game theory. Suppressing a decentralized network requires sustained coordination among numerous government actors and overcoming free-rider problems.

Any single government that permits cryptocurrency while others ban it potentially captures economic activity and innovation. This creates incentives for governments to defect from coordinated suppression efforts.

Additionally, enforcement costs for bans on decentralized technologies are substantial. Governments must monitor internet traffic, prosecute peer-to-peer traders, block exchanges, and constantly adapt as participants develop new methods to circumvent restrictions. These costs must be weighed against benefits of suppression, which may be uncertain.

If cryptocurrency adoption in one's jurisdiction is modest, dedicating significant resources to combating it may not be cost-effective. But if adoption is substantial, suppression has already failed.

For populations in emerging markets, this game theory operates in their favor. Governments face difficult choices about whether to embrace cryptocurrency and attempt to regulate it productively, or to oppose it and watch activity move underground and offshore. Neither option eliminates cryptocurrency entirely. As long as cryptocurrency provides utility that traditional financial systems don't, demand persists.

Youssef's observation that "decentralization further makes it more resilient" captures the strategic advantage of distributed systems. Centralized systems can be targeted efficiently. Distributed systems require attacking many points simultaneously, a much more difficult task. In the contest between governments attempting to control financial access and populations seeking alternatives, decentralization shifts advantages toward the populations.

The Path Forward – Sustainable Financial Inclusion

The examination of cryptocurrency's role in emerging markets reveals both promise and problems. Moving forward requires acknowledging what's working, addressing what isn't, and developing approaches that maximize cryptocurrency's potential for financial inclusion while mitigating risks and harms.

What's Working: Successful Models

Certain patterns emerge from regions and platforms where cryptocurrency has most successfully served financial inclusion goals. Understanding these successes can guide efforts to replicate them elsewhere.

Mobile-first approaches have proven essential. In markets where smartphone penetration exceeds laptop or desktop computer ownership, cryptocurrency services designed primarily for mobile use see greater adoption.

Applications with intuitive interfaces requiring minimal technical knowledge enable broader participation. QR codes for addresses eliminate error-prone manual address entry. Biometric authentication provides security without requiring users to manage complex passwords.

Peer-to-peer trading platforms that connect buyers and sellers locally have created on-ramps and off-ramps between cryptocurrency and local currencies. These platforms enable users to convert between fiat and crypto using locally available payment methods that international exchanges don't support. While peer-to-peer trading introduces certain risks, it solves the critical problem of local access that often blocks adoption.

Integration with existing mobile money systems shows promise in East Africa. Kenya's M-Pesa demonstrated that mobile money could achieve massive adoption even among previously unbanked populations. Building bridges between cryptocurrency and M-Pesa allows users to leverage familiar systems while accessing cryptocurrency's benefits for cross-border transfers and savings. Other mobile money systems in the region have similar potential.

Community-driven adoption, where respected local figures educate and assist populations in accessing cryptocurrency, helps address technical literacy barriers. Rather than expecting users to independently navigate unfamiliar systems, successful models embed support within communities. This can take forms ranging from informal peer assistance to more structured programs organized by exchanges or NGOs.